Many people, when you tell them you’re thinking of going vegan, want to know where you’re going to get your protein. You may even get a few comments like, “Don’t you know if you go vegan you’ll get like a protein deficiency!” Which is not a thing, by the way.

But wondering whether or not you can find enough quality protein on a vegan diet is a valid inquiry. In fact, I commend you for being astute enough to research this topic, because there’s no doubt that many people on the vegan diet neglect their protein intake.

So, what is the best source of protein on a vegan diet?

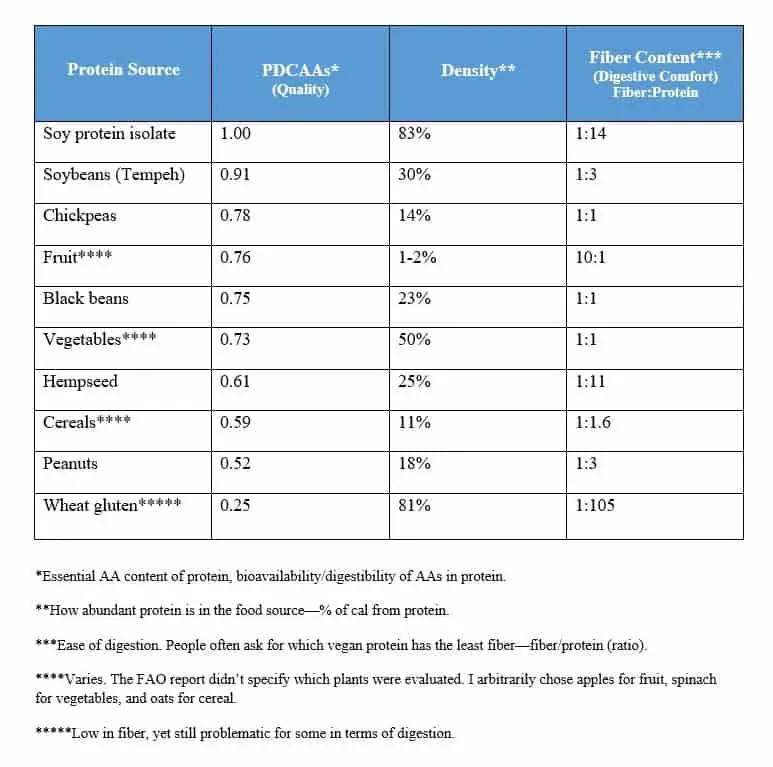

In terms of protein quality (per PDCAAS – the gold standard in protein quality scoring), the single best source is soy.1 In terms of density (foods having the highest % of calories from protein), mock meats, protein powders, and legumes are among the best sources.

As for quality, if you consume a wide variety of plant proteins (legumes, rice, wheat, potatoes, etc.) then you needn’t worry about the single best source.

Anyway, that’s the short answer. Like any good answer, the long version is: it depends. You see, protein quality isn’t the only factor to consider. There’s the quality of the protein itself (how complete the amino acid profile is), but what about the food source? A food item could have the best amino acid profile in the world, but what if it only has 2 grams per 1000 calories? (an exaggeration, but you get the idea).

Also, the “best” vegan protein source depends on your goal. Do you want to lose weight? Are you looking to eat for longevity? (for anti-aging restricting methionine-containing proteins may be beneficial).

Additionally, protein quality can be further subdivided into amino acid profile and digestibility/bioavailability. There’s also GI comfort to consider. You may not tolerate certain plant protein sources that would otherwise be great in terms of protein quality or density.

You also have to consider the lysine content of plant foods. Lysine is an essential amino acid (EAA) that’s often lacking in vegetarian and vegan diets.

Protein Density

This is important to consider given that while most plant foods have some amount of protein in them, the density (grams of protein per calorie in this case) varies quite significantly. Many sites list density by weight. What I mean is the % of calories from protein that a given food has. The weight of the food means nothing for our purposes as water and fiber can vary quite disparately.

You’ll find countless articles online with titles like, “The top 10 vegan sources of protein.” Then they’ll rattle off various grains, and legumes. The problem is, if you rely on many of the sources that are commonly cited, you’ll end up eating far above your calorie needs.

For example, say you need 60 grams of protein. One of the more dense sources of vegan protein that’s commonly prescribed is quinoa, a grain that’s risen in popularity over the last few years. Sites will say it’s just packed with protein—and that it’s a protein “powerhouse.”

Let’s say that you go with foods having a protein density roughly equivalent to quinoa. You’d be eating upwards of 2600 calories daily just to get enough protein!

What about all the other nutrients that you need? And if you’re a bodybuilder who’s shooting for 1 gram of protein per pound of bodyweight (a common prescription for those trying to gain muscle), then god help you! No, no, no, when it comes to the vegan diet, real protein density is your friend.

Don’t get me wrong, many plant sources of protein are much denser than quinoa. But the above point is just to illustrate that the specific source does matter. And unfortunately, many sites just don’t emphasize this enough—often splitting the difference between quinoa and tofu. I’ll continue with this point a bit further down under protein quality.

First, Determine If Protein Density Should Be a Goal

Who may need to prioritized density?

- Those who are trying to lose weight. When you want to lose weight, you’ll need to restrict calories. The problem is, even though you’ll be restricting calories (cutting back on food), protein requirements don’t change. If anything you’ll want to up your protein intake just a bit when in a calorie deficit. For this reason, you’ll want to cram more protein into a smaller calorie allotment.

- Bodybuilders. You guys have higher protein requirements than the average person. So, as in the weight loss scenario, you’ll be needing a higher protein to calorie ratio. If you rely on sparse protein sources, you’ll end up not getting enough protein or eating way above your calorie needs—you’ll get fat sooner, and have to cut your bulking cycle short to burn off the excess fat.

- Choosey eaters. Those who for whatever reason are consistently falling short of meeting their protein requirements. Your food preferences may be characteristically low in protein. Maybe you’re more of an ethical vegan and less into the health/wellness scene. If so, you may be eating a lot of cereal and pop tarts, and foods that are generally lower in protein. Some folks eat a lot of nuts and seeds. Nuts and seeds do contain protein, but they’re not protein dense because they contain fat which has twice the calories gram for gram than protein. Anyway, this brings us to the next point.

Secondly, You’ll Need to Determine Your Individual Protein Needs

You’ll need to determine your protein needs before deciding on specific sources. Unless you’re an athlete (think strength training, bodybuilding, etc.), or you’re calculating protein needs for your child, this isn’t too variable. It comes to 56g and 46g of protein per day for men and women, respectively. Alternatively, you can use 0.8g/kg for both men and women.2

Below I’ve listed a comprehensive list of protein requirements per age and gender. I’ve included protein needs for children and even infants because again, many people are interested in raising their kids on a well-planned vegan diet.2

Kids2

- Boys and girls 1-3 years: 13g/day

- Boys and girls 4-8 years: 19g/day

- Boys and girls 9-13 years: 34g/day

Adolescents (14-18 years)2

- Guys: 52g/day

- Gals: 46g/day

Adults (19 years and over)2

- Men: 56g/day

- Women: 46g/day

If you’re a bodybuilder, then you’ll be aiming a bit higher—1 gram per pound of body weight, or whatever the current recommendations are. There are tons of good bodybuilding info sources out there on how much protein you should be getting that are equally applicable to vegans.

Vegan Protein Density Ranking

Values are listed highest to lowest as a % kcal from protein:3-27

- Protein powders: ~83-84% for pea and soy protein isolates (two popular proteins). That’s from a nutrition database, but I’ve seen higher. Even if you’re not a fan a protein powders, you have to admit that they take the vegan cake when it comes to density. They start with a relatively dense source of protein, then strip away everything else. Can’t get much denser than that.

- Vital wheat gluten: 81%

- Peanut flour, defatted (PB2, etc.): ~56%. I love this stuff. Not a great amino acid spread, but remember we’re talking density at this point.

- Nutritional yeast: ~55%

- Seaweed, spirulina, dried: ~48%

- Tofu: ~40-48%

- Tempeh: ~33%

- Lentils: ~26%

- Hempseed: ~25%

- Black beans: ~23%

- Green peas (cooked): ~22%

- Whole wheat bread: ~20%

- Pinto beans (canned): ~19%

- Teff and spelt (cooked): both ~15%

- Chickpeas and quinoa (canned, cooked): both ~14% kcal from protein. Both are considered real protein “powerhouses” according to many sources.

- Amaranth (cooked): ~13%

- Chia seeds and oats (raw): both ~11%

- Mixed nuts: ~10%

- Brown long-grain rice (cooked): ~8%

- Potatoes (baked): ~7%

The above is referenced with data from nutritiondata.self.com.

Protein Quality: Digestability and Bioavailability

First, we’re going to talk about the importance of protein source when it comes to getting the amino acids into your body in the first place.

Bioavailability is a subcategory of digestibility/absorption, but for our purposes, you can consider them the same thing.28

Here we’re concerned with the degree to which your body can use the ingested nutrient. When you eat a protein-containing food, it doesn’t matter how great the amino acid composition of the protein in the food is if you can’t absorb the protein.

If a nutrient can’t be digested and/or absorbed, it will just pass through GI tract unutilized.

So, continuing with the quinoa example above (not sure why I’m picking on this particular grain): above we talked about how one would need upwards of 2600 calories to get enough protein in a given day from quinoa (or an equivalent source) alone.

Well, that was just in terms of density. Since a significant portion of the protein in quinoa isn’t even available, you’d need in excess of 4000 calories to achieve your protein needs.21

It’s not just quinoa. Unfortunately, most plant sources of protein aren’t particularly great in this area. Animal proteins are implicated in the pathophysiology of a number of chronic diseases conditions. But one must give the devil its due. Animal proteins have been found to be from 90% to 99% digestible, compared to the humble 70% to 90% digestibility rate of plant proteins.29

The proteins in meat and cheese, for example, have a digestibility of about 95%, while eggs are a whopping 97% digestible. Soybeans are the superstars of plant proteins when it comes quality—in food product form more so than whole bean form. While cooked split peas are only about 70% digestible, tofu (derived from soybeans) rivals animal protein sources with a digestibility rate of about 90%.29

Vegan Protein True Digestibility Ranking (Best to Worst):

The data on digestibility of specific proteins and amino acids are much less abundant than the density data, but I’ll list what I was able to find.28,29

- Soy protein isolate: 98%

- Peanut: 96%*

- Wheat gluten: 95%

- Rice and tofu: 90%

- Rolled oats: 88%*

- Wheat: 87%

- Lentil (autoclaved): 85%*

- Mung bean (cooked): 82%

- Corn: 81%

- Pinto bean (canned): 79%*

- Barley and sunflower seed: 78%

- Kidney beans (cooked): 74%

- Wheat bran (cereal) and field beans (cooked): 73%

- Peas (cooked): 72%

- Soybean (cooked): 68%

- Potato (dehydrated): 56%

- Coconut (extracted): 54%

*These values were taken in rats, not humans. But that’s the closest estimate.

Protein Quality: Amino Acid Profile

Now that we have the plant proteins digested and the AAs absorbed, we can talk about the suitability of the AAs swimming around in our bloodstream. Why might they not be suitable? As humans, we need nine essential amino acids (EAAs) from the food we eat. These AAs are essential in that our bodies can’t create them, yet still need them—thus they must come from the diet.30

Unfortunately (in terms of convenience in choosing food choices), not all proteins are created equal when it comes to having a nice even distribution of EAAs that we as humans need for certain functions. A given protein may have TONS of a needed building block, but very little to none of another.

To ensure that you, as a vegan, get the full range of needed amino acids in the right quantities, you can do one of three things:

- The first is to consume ample amounts of the few complete plant proteins out there: soy protein. That’s right, not only is soy reasonably digestible for a plant protein, but it’s also made up of a nice, even mix of the proteins we need.31 Unlike most other proteins in the plant kingdom, soybeans contain the full spectrum of essential amino acids in sufficient ratios.32 Many people don’t like soy or don’t tolerate it well, but if you’re not one of these people, then take advantage of this miracle bean!

- The other option is to purchase a protein powder made of complementary proteins. The good news is that vendors do the research for you, and pair up the complementary amino acid sources. That’s one less headache for you.

- And finally, you can just eat a wide variety of plant protein sources—legumes, nuts, beans, rice. This is probably the best option—at least it’s my favorite. You’ll get the needed distribution of amino acids, though hitting your target protein needs for the day may prove to be difficult. Or at least you’ll need to pay attention, and not just play it by ear so to speak.

It’s Story Time: The Importance of Essential Amino Acids

Just to drive home the importance of ensuring an ample intake of EAAs, I’ll finish off the section on essential amino acids with this tragic true story. Back before people fully understood the importance of amino acid composition, there was a diet known as the “Last Chance Diet,” wherein adherents had to eat a super low-calorie diet to shed fat as quickly as possible.

The first mistake was that they ate about 300-400 calories per day. And while they were correct in assuming that they’d need to get 100% of their calories from protein at such a caloric deficit, the author of the diet had the adherents get all of their protein from collagen—a notoriously terrible source of protein in terms of amino acid content. It ended up costing the lives of several adherents as many died of heart loss.33

Vegan Protein EAA Content Ranking

Ranking the EAA quality of a protein gets complicated because methods of determining the quality of a protein per EAA content relies on what’s known as chemical score.

Chemical score evaluates specific AA content of a given food in relation to a person’s individual requirements of the AA—the latter of which depends on age, etc.

Fortunately, we need not worry chemical score because the experts have crunched the numbers for us in what’s known as the protein digestibility corrected amino acid score (PDCAAS). A mouthful, I know.

How Overall Protein Quality Is Determined

PDCAAS is the method of choice these days when it comes to comparing the protein quality of different food source. It takes into account both the digestibility/bioavailability as well as the EAA content.34

This method of evaluating protein quality is so widely used that foods intended for individuals beyond age 1 and foods having health claims have to use the scoring method to provide info on the product’s food label.

How does it work? The limiting amino acid is the AA in shortest supply compared to what the body needs. The PDCAAS method compares the amount of the limiting AA of a test protein (chickpeas, let’s say) to the amount of the same AA in a reference protein (egg usually). This value is then multiplied by the protein’s digestibility (the values we covered above).

Gropper, Sareen S.; Smith, Jack L.. Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism (Page 239).

Vegan Protein Overall Quality Ranking:

Best to worst – PDCAA values.1,34,35

- Soy protein (isolate): 1.00

- Soybeans: 0.91

- Chickpeas: 0.78

- Fruit: 0.76

- Black beans: 0.75

- Vegetables: 0.73

- Hempseed: 0.61

- Cereals: 0.59

- Peanuts: 0.52

- Wheat gluten: 0.25

Putting It All Together

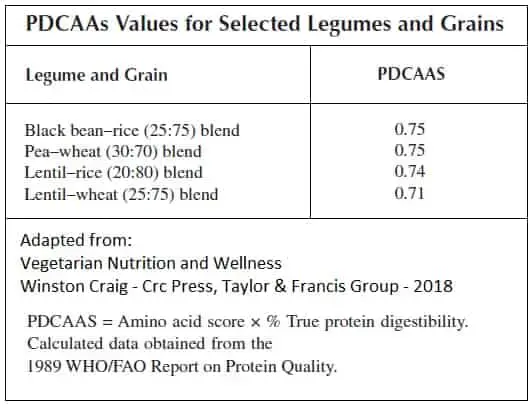

Complementary Proteins

If you’re not a huge fan of some of the higher scoring proteins, fear not. As I mentioned in the opening of the article, variety goes a long way when it comes to meeting standards for protein quality. When you get your protein from a wide range of sources, the quality kind of takes care of itself.

Additionally, there are especially synergistic combinations of proteins—what we call complementary proteins.

Two or more plant proteins having complementary AA profiles improve protein quality. For example, sulfur-containing AAs (those having methionine and cysteine) tend to be the limiting AAs in legumes, while cereals (rice and wheat) tend to come up short when it comes to lysine.

However, combining rice and beans increases the overall PDCAAS values.36

This is likely the phenomenon by which many populations in developing countries achieve their needed AAs. For example, populations consuming mostly plant-based foods often eat complementary proteins together at each meal—such as legumes and soy in Asia.37

Here are some examples

A Note on Protein Source Tolerability

After all that science-y stuff, we’re now left with one more thing to consider. What you might call the “where do I get vegan protein from a source that doesn’t involve beans” factor. We’ll call it the gas factor.

Now, this doesn’t apply to everyone. I for one have a cast-iron stomach and can eat anything. But, food intolerances are super common in on the plant-based scene.

Now, as I go over in my article, Initial Gas on the Vegan Diet, some gas is normal and can even be indicative of healthy processes. But, acquiring a good portion of one’s protein from certain sources—namely those involving what are known as FODMAPs—can be a bit much for some. And understandably so.

For those of you who fall into this category, you’ll want to pay attention to how certain food sources affect your digestion. The protein itself may digest plenty well enough to be absorbed and assimilated into your tissue, but if you have to endure loud and uncomfortable GI symptoms along the way, it may hardly be worth it.

This one is highly variable, so ranking, in this case, is difficult. Again, you’ll need to pay attention to the foods you tolerate best.

Anyway, hopefully, that gives you an idea of how to best go about getting adequate protein on a 100% plant-based diet. Perhaps at some point, I’ll write an in-depth article on protein quality.

Until next time.

References

- Jay R. Hoffman and Michael J. Falvo. Protein – Which is Best? J Sports Sci Med. 2004 Sep; 3(3): 118–130.

- Dietary Reference Intakes For Calcium and Vitamin D – NCBI Bookshelf. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Review Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin D and Calcium – https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK56068/table/summarytables.t4/?report=objectonly

- Pea Protein Nutrition Facts & Calories. https://nutritiondata.self.com/facts/custom/630722/0?print=true

- Soy Protein Isolate Nutrition Facts & Calories. https://nutritiondata.self.com/facts/legumes-and-legume-products/4389/2

- Vital Wheat Gluten Nutrition Facts & Calories. https://nutritiondata.self.com/facts/cereal-grains-and-pasta/7738/2

- Peanut Flour, Defatted Nutrition Facts & Calories https://nutritiondata.self.com/facts/legumes-and-legume-products/4367/2

- Nutritional Yeast Nutrition Facts & Calories. https://nutritiondata.self.com/facts/custom/861742/2

- Seaweed, Spirulina, Dried Nutrition Facts & Calories. https://nutritiondata.self.com/facts/vegetables-and-vegetable-products/2765/2

- Tofu, Firm, Prepared with Calcium Sulfate and Magnesium Chloride (nigari) Nutrition Facts & Calories. https://nutritiondata.self.com/facts/legumes-and-legume-products/4393/2

- Tofu https://www.walmart.com/ip/Mori-Nu-Extra-Firm-Shelf-Stable-Tofu-12-3-Oz/38282148

- Tempeh Nutrition Facts & Calories. https://nutritiondata.self.com/facts/legumes-and-legume-products/4381/2

- Lentils, Mature Seeds, Cooked, Boiled, Without Salt Nutrition Facts & Calories. https://nutritiondata.self.com/facts/legumes-and-legume-products/4338/2

- Hemp Seed (shelled) Nutrition Facts & Calories. https://nutritiondata.self.com/facts/custom/629104/2

- Beans, Black, Mature Seeds, Cooked, Boiled, Without Salt Nutrition Facts & Calories. https://nutritiondata.self.com/facts/legumes-and-legume-products/4284/2

- Peas, green, Canned, No Salt Added, Drained Solids Nutrition Facts & Calories. https://nutritiondata.self.com/facts/vegetables-and-vegetable-products/2888/2

- Bread, Whole-wheat, Commercially Prepared Nutrition Facts & Calories. https://nutritiondata.self.com/facts/baked-products/4876/2

- Beans, Pinto, Mature Seeds, Canned Nutrition Facts & Calories. https://nutritiondata.self.com/facts/legumes-and-legume-products/4313/2

- Teff, Cooked Nutrition Facts & Calories. https://nutritiondata.self.com/facts/cereal-grains-and-pasta/10358/2

- Spelt, Cooked Nutrition Facts & Calories. https://nutritiondata.self.com/facts/cereal-grains-and-pasta/10356/2

- Chickpeas (garbanzo Beans, Bengal Gram), Mature Seeds, Canned Nutrition Facts & Calories. https://nutritiondata.self.com/facts/legumes-and-legume-products/4327/2

- Quinoa, Cooked Nutrition Facts & Calories. https://nutritiondata.self.com/facts/cereal-grains-and-pasta/10352/2

- Amaranth Grain, Cooked Nutrition Facts & Calories https://nutritiondata.self.com/facts/cereal-grains-and-pasta/10640/2

- Seeds, Chia Seeds, Dried Nutrition Facts & Calories. https://nutritiondata.self.com/facts/nut-and-seed-products/3061/2

- Cereals, Oats, Instant, Fortified, Plain, Dry [instant Oatmeal] Nutrition Facts & Calories. https://nutritiondata.self.com/facts/breakfast-cereals/1599/2

- Nuts, Mixed Nuts, Dry Roasted, with Peanuts, Without Salt Added Nutrition Facts & Calories. https://nutritiondata.self.com/facts/nut-and-seed-products/3125/2

- Rice, Brown, Long-grain, Cooked Nutrition Facts & Calories https://nutritiondata.self.com/facts/cereal-grains-and-pasta/5707/2

- Potato, Baked, Flesh and Skin, Without Salt Nutrition Facts & Calories https://nutritiondata.self.com/facts/vegetables-and-vegetable-products/2770/2

- FAO (2011). Protein Quality Evaluation in Human Nutrition: The assessment of amino acid digestibility in foods for humans and including a collation of published ileal amino acid digestibility data for human foods. Document prepared by Dr Shane Rutherfurd of the Riddet Institute, Massey University, New Zealand.

- Gropper, Sareen S.; Smith, Jack L. Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism (Page 239).

- Protein and Amino Acids. National Research Council (US) Subcommittee on the Tenth Edition of the Recommended Dietary Allowances – https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK234922/

- Messina, M. Legumes and soybeans: overview of their nutritional profiles and health effects. Am J Clin Nutr (1999) 70 (suppl): 439s-450s.

- Young VR. Soy protein in relation to human protein and amino acid nutrition. J Am Diet Assoc. 1991;91(7):828-35.

- See the 5 November 2018 comment at Talk:Protein-sparing modified fast. And see also: Isner, JM; Sours, HE; Paris, AL; Ferrans, VJ; Roberts, WC (December 1979). “Sudden, unexpected death in avid dieters using the liquid-protein-modified-fast diet: observations in 17 patients and the role of the prolonged QT interval” (PDF). Circulation. 60 (6): 1401–1412.

- Schaafsma G. The Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS)–a concept for describing protein quality in foods and food ingredients: a critical review. J AOAC Int. 2005 May-Jun;88(3):988-94.

- House, J (2010). “Evaluating the quality of protein from hemp seed (Cannabis sativa L.) products through the use of the protein digestibility-corrected amino acid score method” (PDF). J. Agric. Food Chem. 58: 11801–7

- Pulse Canada. 2017. Protein quality of cooked pulses. Winnipeg, Mannitoba: Pulse Canada.

- Mangels R, Messina V, Messina M. 2011. The Dietitian’s Guide to Vegetarian Diets. Jones & Bartlett Publishers.