In this article, we’re going to talk about metabolic syndrome, or syndrome x, which is a cluster of atherogenic risk factors (metabolic abnormalities increasing one’s risk of heart disease).

C

As for individual risk factors for MetS, according to Rizzo et al., vegetarian diets reduce the risk of every individual risk factor of the metabolic syndrome with the exception of increasing HDL cholesterol (for which only exercise reliably helps). Namely, vegetarian diets are associated with lower waist circumference, and lower triglyceride concentrations, total and LDL cholesterol, blood pressure, and blood sugar.37,49,50

Researchers Turner McGrievy G and Harris M seem to agree. They conducted a review of the current literature on plant-based diets and metabolic syndrome. According to Turner-McGrievy and Harris, “these studies, conducted mostly in Asian populations, yielded varying results. The majority, however, found better metabolic risk factors and lowered risk of metabolic syndrome among individuals following plant-based diets, as compared with omnivores.”1

So, in this article, I’ll touch on some of the key elements of plant-based diets associated with a reduced risk of metabolic syndrome. In order to fully appreciate the positive benefits, we’ll, of course, need to go over exactly what the condition is, and then talk about where it is that a healthy, whole food vegan diet can come into play.

So, What Is Metabolic Syndrome?

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a multidimensional risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD). If something’s a risk factor for a disease, then having that something means that you have an elevated risk for developing the said disease. So, hypertension (high blood pressure) is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. So is dyslipidemia (high cholesterol, triglycerides, etc.).

What many people don’t know is that aside from individual risk factors for CVD (hypertension, high cholesterol), there’s also a characteristic grouping of individual risk factors that form what you could think of as a mega risk factor: in this case, metabolic syndrome.

In 1977, Gerald B. Phillips put forward the concept that risk factors for a heart attack tend to occur as a “constellation of abnormalities” (glucose intolerance, hyperinsulinemia, high cholesterol and triglycerides, and hypertension).

In doing, he suggested that there must be some common cause or factor underlying all of these abnormalities that lead to CVD. He came up with this idea but didn’t quite have the common factor figured out. He thought it may have something to do with sex hormones.2,3

Along comes another Gerald in 1988—Gerald M. Raven—who suggested insulin resistance could be the common factor accounting for the characteristic clustering of CVD risk factors.

Insulin resistance is when the body makes plenty of insulin (unlike type 1 diabetes), but it’s less sensitive to some of its effects—i.e. the insulin can’t really do its primary job very well. He named the constellation of abnormalities “syndrome X.” Don’t ask me why he decided to give such a sexy name to such a terrible condition.

Anyway, syndrome X is synonymous with metabolic syndrome. Now, he didn’t have it all figured out but he was definitely on the right track.4

Currently, five metabolic risk factors are thought to comprise metabolic syndrome:5,6

- Atherogenic dyslipidemia

- Raised blood pressure

- Elevated glucose

- Proinflammatory state

- Prothrombotic state

Confusingly, there are several related conditions that are considered risk factors for metabolic syndrome. You might say they’re risk factors for a big risk factor encompassing several risk factors for CVD.5

- Obesity—especially abdominal obesity.*

- Low levels of physical inactivity

- “Atherogenic” diet—fancy way of saying a diet conducive to CVD. Hint: where the vegan diet comes to the rescue.

- Primary insulin resistance

- Hormone-related factors

- Old age

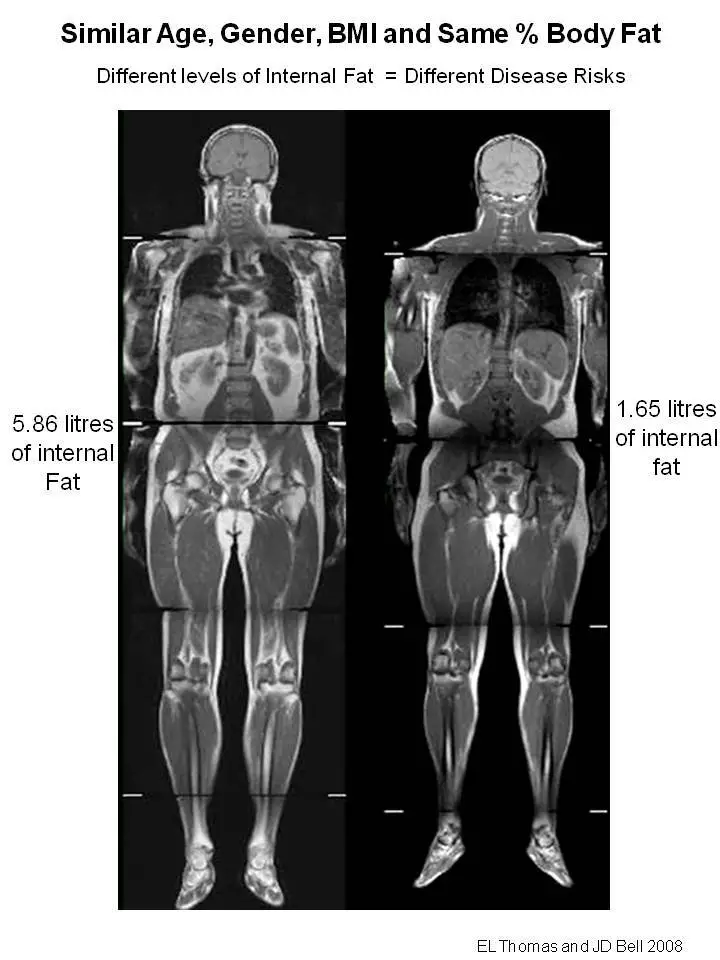

*Have you ever known someone who had a gut that stuck out really far, yet was hard as a rock to the touch? Was it disproportionate to the rest of the body? That’s abdominal obesity or central adiposity. It’s a pattern of fat storage that’s characteristic of someone with insulin resistance. Unlike subcutaneous fat, visceral fat is deeper in the abdominal cavity insulating organs, etc. Because it’s behind the abdominal wall, it’s hard.

Obesity and insulin resistance are the two main risk factors for metabolic syndrome.

Just How Indicative Is It of CVD Risk?

Let’s just put it this way: have you ever heard of LDL cholesterol? Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, or “bad cholesterol.” High LDL cholesterol is thought of by many as the main risk factor for CVD.

It just so happens that The National Cholesterol Education Program’s Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III) put out a report wherein risk-reduction for metabolic syndrome was classified as a coequal partner of LDL cholesterol when it came to prioritizing risk-reduction therapies.

I.e. they considered addressing metabolic syndrome to be equally important as addressing high LDL in the area of risk-reduction therapies.7

Aside from CVD, metabolic syndrome is also a risk factor for the development of type 2 diabetes. This should come as no surprise given that one of the underlying factors of MetS is insulin resistance.

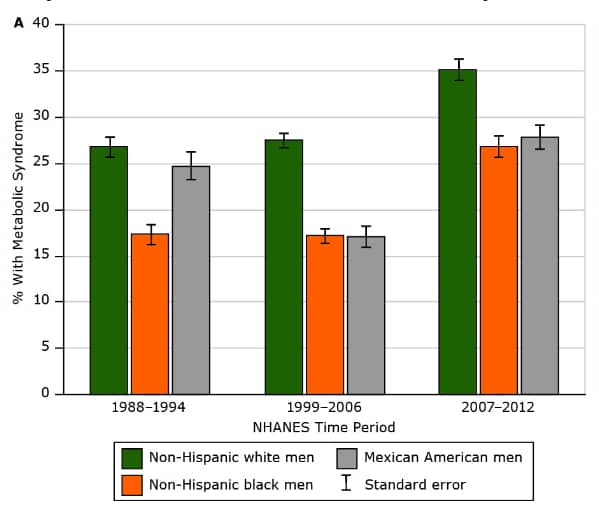

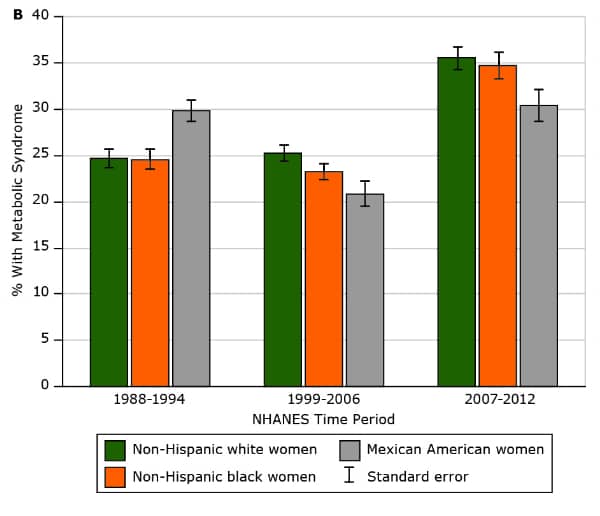

Just How Widespread Is the Problem?

In the US, approximately one in four adults have metabolic syndrome.8

Worldwide, 20% to 25% of adults have the condition.9

CDC Preventing Chronic Disease

https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2017/16_0287.htm

Treatment and Management of Metabolic Syndrome

Because metabolic syndrome is a cluster of metabolic dysfunctions, treatment will, of course, resemble the measures taken to address the individual abnormalities that comprise MetS—high cholesterol, hypertension, etc.

I.e. MetS is addressed via lifestyle therapies, including various approaches to improving dietary intake, insulin sensitivity, lipids, body weight, and blood pressure.10

Metabolic Syndrome and the Vegan Diet

Folks with metabolic syndrome tend to consume diets higher in empty calories (fried foods, etc.) and lower in fruits, vegetables, and fiber.11

And according to Turner-McGrievy and Harris, “plant-based diets, such as vegan and vegetarian diets, are a dietary strategy that may be useful in treating and preventing the development of metabolic syndrome.”1

According to the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND), “studies have demonstrated that well-planned vegan and vegetarian diets can provide adequate nutrition and may have health benefits for disease prevention and treatment.”12

Benefits of the Vegan Diet for MetS Prevention

What I’ll do for the rest of the article, is outline the specific ways in which a healthy, whole food vegan diet can help prevent metabolic syndrome. For these purposes, I’ll be using vegan and plant-based interchangeably.

It’s important to note that while many randomized controlled trials (RTCs) have examined the effects of vegan and vegetarian diets on numerous endocrine-related conditions (T2DM, PCOS, etc.) there are yet to be any clinical trials examining plant-based diets for the prevention/treatment of metabolic syndrome.13,14

Vegans and Vegetarians Have Lower BMIs

People who follow vegetarian and vegan diets have lower body mass indices (BMIs), compared to nonvegetarians.15,16

This, of course, suggests that there must be aspects inherent to plant-based eating patterns that are conducive to achieving and maintaining a healthy body weight. As we know from above, obesity is one of the few risk factors for developing MetS.

And indeed there are. Whole plant foods are high in volume/bulk and low in calories—what’s known as low caloric density.

Proof? Various clinical trials have tested vegan and vegetarian diets for weight loss, and have demonstrated significant improvements in body fat status.

That’s right, the vegan diet has been used with success for weight loss and maintenance.16,17

Lower T2DM Incidence Among Vegans and Vegetarians

Those following healthy plant-based diets have a lower prevalence of type 2 diabetes (T2DM).15,18,19

Like with obesity, clinical trials have tested plant-based diets for helping with glycemic control, and have shown significant improvements in helping regulate blood glucose levels. And that’s in comparison with other conventional approaches to glycemic control—low energy diets, etc.20

Proven Efficacy of Vegan Diets in Improving Lipid Profile

Over the last few decades, CVD mortality rates in the US have declined. About half of the observed decline in CVD mortality is attributed to medical therapies (e.g. secondary prevention, heart failure, treatments, etc.) while the other half is attributed to improvements in modifiable risk factors—improvements in blood pressure, cholesterol, dietary habits, physical activity levels, and smoking prevalence.21

And you guessed it: clinical trials using plant-based diets have shown efficacy in reducing cardiovascular risk factors, as compared with conventional dietary/lifestyle approaches (e.g. reduced fat diets, weight loss, etc.).22

Vegans Have Lower Intakes of Saturated Fat

The results are somewhat mixed, but some studies have shown saturated fats (SFAs) to be associated with an increased risk of developing MetS.23,24

What’s this have to do with a vegan diet? While following the vegan diet doesn’t necessitate SFA restriction from plant oils, a healthy whole food vegan diet is one that’s low in empty calories, and by extension low in SFAs.

Experimental and observational studies consistently show the vegan diet to be characteristically low in SFAs compared to omnivorous diets.25-30

Why is this important? Because remember that MetS is a cluster of CVD risk factors, one of which being hypercholesterolemia. What are the general recommendations for folks who want to avoid high cholesterol?

The American Heart Association (AHA) recommend one maintain a diet with less than 10% of calories coming from SFAs.31

The U.S. Dietary Reference Intakes state that SFA intake should be “as low as possible while consuming a nutritionally adequate diet.”32

Vegans Don’t Consume Red Meat

You may have heard red meat, especially processed red meat, has been linked to colorectal cancer. Well, red/processed meat consumption has also been associated with an increased risk of developing MetS and T2DM.33-36

As with cancer, the less you eat the better. While those on vegetarian and flexitarian diets can see an improved risk of certain chronic diseases linked to meat consumption, only vegans eliminate all meat—and thus would be expected to experience the most benefit in this area.

Even individuals following semi-vegetarian or pesco-vegetarian diets consume significantly less animal protein than do omnivores, although intakes are even lower among those following vegetarian or vegan diets.25

Turner McGrievy G and Harris M speculate that this dose-response pattern of meat intake may be one explanation for the same pattern shown amongst the diet groups in the Rizzo et al. study. In the study by Rizzo et al, rates of metabolic syndrome were highest in omnivores and lowest in vegetarians, with intermediate risk seen in semi-vegetarians.1,37,18

Plant-Based Diets Are High in Fiber

Higher fiber intakes are associated with a decreased risk of developing MetS.38-40

Significance? The vegan diet precludes all foods of animal origin. Animal foods are the most common sources of protein, an essential nutrient.

Well, when you remove the single biggest source of protein, you leave a giant protein void in your diet waiting to be filled with plant sources of protein… which happen to be loaded with fiber. Vegan sources of protein include legumes (lentils, peas, beans), nuts, seeds, and soy products.

Many common vegan sources of protein provide fiber and protein in a 1 to 1 ratio.41

Plant-Based Diets Are High in Fruits and Veggies

It should come as no surprise that vegans tend to have higher intakes of fruits and vegetables.25-29,42-44

Significance? High intake of fruits and vegetables is associated with a reduced risk of metabolic syndrome.45,46

Why? No one knows. It may be because fruits and veggies provide individuals with important phytonutrients and antioxidants, which may help in preventing inflammation.45

It may be because fruits and veggies are good sources of fiber as mentioned above, which as we know can help in preventing MetS.46

A Whole Food Focus

Thus far, most studies examining the link between diet and metabolic syndrome have primarily focused on single nutrients (fiber, etc.).47

This is a bit of an antiquated approach. These days, the relationship between diet and health outcomes is seen as a rather mysterious phenomenon. Especially when it comes to the beneficial effects of some foods on health.

While a straight line can often be drawn from a deleterious food component to a negative health outcome (e.g. trans fat and CVD), much of the current research on plant-based foods and health tend to focus on food groups rather than specific nutrients.

Why? Because when researchers isolated compounds thought to be healthy and administered them in isolation (specific antioxidant pills or fiber supplements), the results were often lackluster. These days, it’s thought that the nutrients present in plant foods may work in synergy with each other, or that the food matrix itself may play a role.48

But, I bring this up because in mentioning certain food groups as potentially beneficial in preventing metabolic syndrome, I’m not able to point to any one nutrient that plays a definitive role in the protective effects seen. I cover some specific nutrients but keep in mind that the main focus should always be on the whole plant foods.

Anyway, that does it for now. Hopefully, that gives you an idea of what metabolic syndrome is, and what a healthy whole food vegan diet can do to help prevent it.

References

- Turner McGrievy G and Harris M. Key elements of plant-based diets associated with reduced risk of metabolic syndrome. Curr Diab Rep. 2014;14(9):524

- Phillips GB (July 1978). “Sex hormones, risk factors and cardiovascular disease”. The American Journal of Medicine. 65 (1): 7–11.

- Phillips GB (April 1977). “Relationship between serum sex hormones and glucose, insulin and lipid abnormalities in men with myocardial infarction”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 74 (4): 1729–33.

- Reaven GM: Banting lecture 1988. Role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes 1988, 37:1595–1607.

- Atlas Of Atherosclerosis and Metabolic Syndrome Scott Grundy – Springer – 2011

- Grundy SM, Brewer Jr HB, Cleeman JI, Smith Jr SC, Lenfant C. Definition of metabolic syndrome: Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation. 2004;109: 433–8.

- National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III): Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation 2002, 106:3143–3421.

- Beltrán-Sánchez H, Harhay MO, Harhay MM, McElligott S. Prevalence and Trends of Metabolic Syndrome in the Adult U.S. Population, 1999–2010. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:697–703.

- Alberti KGMM, Zimmet P, Shaw J. Metabolic syndrome—a new world-wide definition. A Consensus Statement from the International Diabetes Federation. Diabet Med. 2006;23:469–80.

- Eckel RH, Jakicic JM, Ard JD, Miller NH, Hubbard VS, Nonas CA, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC Guideline on Lifestyle Management to Reduce Cardiovascular RiskA Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013

- Baxter AJ, Coyne T, McClintock C. Dietary patterns and metabolic syndrome–a review of epidemiologic evidence. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2006;15:134–42.

- Craig WJ, Mangels AR. Position of the American Dietetic Association: vegetarian diets. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:1266– 82.

- Barnard ND, Katcher HI, Jenkins DJ, Cohen J, Turner-McGrievy G. Vegetarian and vegan diets in type 2 diabetes management. Nutr Rev. 2009;67:255–63.

- Turner-McGrievy GM, Davidson CR, Wingard EE, Billings DL. Low glycemic index vegan or low calorie weight loss diets for women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Randomized Controlled Feasibility Study. Nutr Res. 2014

- Tonstad S, Butler T, Yan R, Fraser GE. Type of vegetarian diet, body weight, and prevalence of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:791–6.

- Turner-McGrievy GM, Barnard ND, Scialli AR. A two-year randomized weight loss trial comparing a vegan diet to a more moderate low-fat diet. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007;15:2276–81

- Ornish D, Scherwitz LW, Billings JH, Brown SE, Gould KL, Merritt TA, et al. Intensive lifestyle changes for reversal of coronary heart disease. JAMA. 1998;280:2001–7.

- Tonstad S, Stewart K, Oda K, Batech M, Herring RP, Fraser GE. Vegetarian diets and incidence of diabetes in the Adventist Health Study-2. Nutr Metab Cardiovas. 2011:1–8.

- Tonstad S, Stewart K, Oda K, Batech M, Herring RP, Fraser GE. Vegetarian diets and incidence of diabetes in the Adventist Health Study-2. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;23:292–9.

- Barnard ND, Cohen J, Jenkins DJ, Turner-McGrievy G, Gloede L, Jaster B, et al. A low-fat vegan diet improves glycemic control and cardiovascular risk factors in a randomized clinical trial in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1777–83.

- Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, et al: Explaining the decrease in U.S. deaths from coronary disease, 1980–2000. N Eng J Med 2007, 356:2388–2398.

- Jenkins DJ, Kendall CW, Faulkner DA, Nguyen T, Kemp T, Marchie A, et al. Assessment of the longer-term effects of a dietary portfolio of cholesterol-lowering foods in hypercholesterolemia. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:582–91.

- Riccardi G, Giacco R, Rivellese AA. Dietary fat, insulin sensitivity and the metabolic syndrome. Clin Nutr. 2004;23:447–56.

- Vessby B. Dietary fat, fatty acid composition in plasma and the metabolic syndrome. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2003;14:15–9.

- Rizzo NS, Jaceldo-Siegl K, Sabate J, Fraser GE. Nutrient Profiles of Vegetarian and Nonvegetarian Dietary Patterns. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2013.

- Clarys P, Deliens T, Huybrechts I, Deriemaeker P, Vanaelst B, De Keyzer W, et al. Comparison of Nutritional Quality of the Vegan, Vegetarian, Semi-Vegetarian. Pesco-Vegetarian and Omnivorous Diet. Nutrients. 2014;6:1318–32

- Clarys P, Deriemaeker P, Huybrechts I, Hebbelinck M, Mullie P. Dietary pattern analysis: a comparison between matched vegetarian and omnivorous subjects. Nutr J. 2013;12:82.

- Turner-McGrievy GM, Barnard ND, Cohen J, Jenkins DJ, Gloede L, Green AA. Changes in nutrient intake and dietary quality among participants with type 2 diabetes following a low-fat vegan diet or a conventional diabetes diet for 22 weeks. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:1636–45.

- Turner-McGrievy GM, Barnard ND, Scialli AR, Lanou AJ. Effects of a low-fat vegan diet and a Step II diet on macro- and micronutrient intakes in overweight postmenopausal women. Nutrition. 2004;20:738–46.

- Mishra S, Barnard ND, Gonzales J, Xu J, Agarwal U, Levin S. Nutrient intake in the GEICO multicenter trial: the effects of a multicomponent worksite intervention. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67: 1066–71.

- Krauss RM, Eckel RH, Howard B, Appel LJ, Daniels SR, Deckelbaum RJ, et al. AHA Dietary Guidelines: Revision 2000: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the Nutrition Committee of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2000;102:2284–99.

- Parker L, Burns AC, Sanchez E. Local Government Actions to Prevent Childhood Obesity. Washington, D.C: The National Academies Press; 2009. http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_ id=12674 Institute of Medicine and the National Research Council of the National Academies.

- Barnard N, Levin S, Trapp C. Meat Consumption as a Risk Factor for Type 2 Diabetes. Nutrients. 2014;6:897–910.

- Azadbakht L, Esmaillzadeh A. Red Meat Intake Is Associated with Metabolic Syndrome and the Plasma C-Reactive Protein Concentration in Women. J Nutr. 2009;139:335–9.

- Damiao R, Castro TG, Cardoso MA, Gimeno SG, Ferreira SR, Japanese-Brazilian Diabetes Study G. Dietary intakes associated with metabolic syndrome in a cohort of Japanese ancestry. Br J Nutr. 2006;96:532–8.

- Babio N, Sorlí M, Bulló M, Basora J, Ibarrola-Jurado N, Fernández-Ballart J, et al. Association between red meat consumption and metabolic syndrome in a Mediterranean population at high cardiovascular risk: Cross-sectional and 1-year follow-up assessment. Nutr Metab Cardiovas. 2012;22:200–7

- Rizzo NS, Sabaté J, Jaceldo-Siegl K, Fraser GE. Vegetarian Dietary Patterns Are Associated With a Lower Risk of Metabolic Syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1225–7.

- Carlson JJ, Eisenmann JC, Norman GJ, Ortiz KA, Young PC. Dietary Fiber and Nutrient Density Are Inversely Associated with the Metabolic Syndrome in US Adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111:1688–95.

- Galisteo M, Duarte J, Zarzuelo A. Effects of dietary fibers on disturbances clustered in the metabolic syndrome. J Nutr Biochem. 2008;19:71–84.

- McKeown NM, Meigs JB, Liu S, Saltzman E, Wilson PWF, Jacques PF. Carbohydrate Nutrition, Insulin Resistance, and the Prevalence of the Metabolic Syndrome in the Framingham Offspring Cohort. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:538–46

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. 2012. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 25. Nutrient Data Laboratory Home Page, http://www.ars. usda.gov/ba/bhnrc/ndl. Accessed February 10, 2014

- Davey GK, Spencer EA, Appleby PN, Allen NE, Knox KH, Key TJ. EPIC-Oxford: lifestyle characteristics and nutrient intakes in a cohort of 33 883 meat-eaters and 31 546 non meat-eaters in the UK. Public Health Nutr. 2003;6:259–69.

- Farmer B, Larson BT, Fulgoni Iii VL, Rainville AJ, Liepa GU. A Vegetarian Dietary Pattern as a Nutrient-Dense Approach to Weight Management: An Analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2004. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111:819– 27.

- Haddad EH, Tanzman JS. What do vegetarians in the United States eat? Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:626S–32

- Esmaillzadeh A, Kimiagar M, Mehrabi Y, Azadbakht L, Hu FB, Willett WC. Fruit and vegetable intakes, C-reactive protein, and the metabolic syndrome. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:1489–97.

- Yoo S, Nicklas T, Baranowski T, Zakeri IF, Yang S-J, Srinivasan SR, et al. Comparison of dietary intakes associated with metabolic syndrome risk factors in young adults: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:841–8.

- Salas-Salvadó J, Guasch-Ferré M, Bulló M, Sabaté J. Nuts in the prevention and treatment of metabolic syndrome. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014

- Yasmine C Probst, Vivienne X Guan, and Katherine Kent. Dietary phytochemical intake from foods and health outcomes: a systematic review protocol and preliminary scoping. BMJ Open. 2017;7(2):e013337.

- Teixeira, R., de, C.M., de, A., Molina, M., del, C.B., Zandonade, E., Mill, J.G., October 2007. Cardiovascular risk in vegetarians and omnivores: a comparative study. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 89 (4), 237–244.

- De Biase, S.G., Fernandes, S.F.C., Gianini, R.J., Duarte, J.L.G., January 2007. Vegetarian diet and cholesterol and triglycerides levels. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 88 (1), 35–39.