You may have noticed that the online vegan community underwent what seemed to be a mass Vexit. This led many people who were considering adopting a vegan diet to question whether it’s a suitable eating pattern for the long term. Maybe it’s just too difficult to adhere to for any length of time.

The difficulty of following plant-based diets varies depending on circumstances. But, the short answer is that, in general, the vegan diet is much more difficult to follow compared to most eating patterns.

Part of the reason people leave the vegan community is that they have false expectations—in terms of health benefits, results, aesthetics, and ease of adherence.

I’ll be outlining some of the challenges in the paragraphs to come, from the trivial to the serious. I think you’ll agree that most challenges only apply to folks who are in very unfortunate circumstances in terms of health and economics.

If you’re WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic) and free of debilitating digestive issues, then you’ll be hard-pressed to come up with a good reason that you can’t follow a 100% plant-based diet.

There was recently a large exit from the vegan community, and I highly doubt that many (if any) had a solid reason for going the way of the omnivore.

While it is generally more difficult to follow a vegan diet compared to other diets, the difficulty at the individual level depends on a number of factors such as where you live—do you live in a forward-thinking city with a hippy whole food health store on every corner? Or do you live in rural Alabama with nothing but a Dollar General in driving distance?

There’s also digestive health—do you have any food intolerances that would make an already restrictive diet even more restrictive?

You get the idea…

What I’ll do here is cover the various barriers to eating healthy. There are many theories of behavior that map on well to the challenges of following plant-based diets, so we’ll use those as a guide to understanding the difficulties you might face when going vegan.

But, before that, we should first answer a basic question.

Just How Difficult Is It to Eat Vegan?

Keep in mind that these data pertain mostly to vegetarian diets—a much less restrictive form of plant-based eating. So, whatever findings studies yield in terms of the difficulty of following vegetarian diets, we can assume it applies doubly to vegan diets.

US News & World Report

The US News & World Report put out a 2016 Best Diet Ranking in which both vegan and semivegetarian (flexitarian) diets were ranked as the #7 best weight loss diets.

Compared to the semi-vegetarian diet, the vegan diet received far lower scores in the category of “easy to follow.”

Almost anyone could follow a flexitarian diet, which is why Meatless Mondays are popular with those unable or unwilling to adhere to a comparatively restrictive dietary pattern.

They preach that absolute adherence isn’t necessary. And when it comes to weight loss, they’re right. One study found subjects counseled to follow a plant-based diet to reduce animal product consumption to be more successful in losing weight—even when they fell short of absolute adherence—compared to subjects assigned to omnivorous weight loss diets.2

However, this is hardly any consolation to those considering the vegan diet for ethical reasons. When something is wrong, it’s wrong. And it makes little sense to consume animal products which contribute to the suffering of sentient beings, when there are other options available.

Vegetarian Diets and Weight Reduction: a Meta-Analysis of RCTs

In 2015, Huang et al. found that when weight loss diets were randomly assigned, adherence to the Weight Watchers diet was 65% while adherence to a low-fat vegetarian diet was only 50%.3

Weight loss diets are hard to stick to. Period. But, I think the results are worth considering, given that the vegetarian diet was compared to Weight Watchers—a very mainstream diet based on a caloric deficit with little restriction of food options.

Don’t get me wrong, not every study has shown vegan diets to have lower adherence rates. For example, in one study of 63 overweight and obese adults, researchers found no significant difference in acceptability or compliance, regardless of whether subjects were assigned an omnivorous, vegetarian, pescetarian, semivegetarian, or vegan diet.2

But, many well-designed studies have. For example, two clinical trials noted attrition rates among participants to be as high as 50% to 67% after 6 months when vegan weight loss diets were prescribed.4,5

I’d like to see more studies of this nature that eliminate calorie deficit as a variable. I.e. we don’t know if participants would drop out due to hunger imposed by a calorie deficit more so than restriction of food choices.

But, it’s hard not to assume food choice restriction to play a role in attrition rates, given that many studies compared compliance in calorically restricted vegan diets vs. mainstream diets (e.g. Weight Watchers).

Barriers to Change: Plant-Based Diet Edition

Experts on consumer behavior talk a lot about what are known as barriers to change: anything that gets in the way of you taking on new desired behaviors. In this case, transitioning to a vegan diet.

The barriers needn’t be real. In fact, the Health Belief Model (HBM) of behavior change has a construct known as “perceived barriers”: any potential negative aspect of a particular health action that may impede one’s undertaking of recommended behaviors.6

When someone thinks of taking on a new behavior, they perform an internal calculus to determine whether or not the new habit would be feasible. It’s like a pro’s and con’s list, but the process takes place unconsciously. The internal dialogue may sound something like:

“It could help me, but it may be expensive, have negative side effects, be unpleasant, inconvenient, or time-consuming.”7

And it doesn’t stop at the adoption of the habit. Doubts about what you’re doing and your own “self-efficacy” in maintaining the new way of life can continue indefinitely.

Remember the great Vexit of 2018. It may still be going on. It seemed that one vegan Youtuber after the other was throwing in the towel usually citing health and digestive reasons. This was after the individuals successfully (or seemingly successfully) implemented the diet anywhere from months to years.

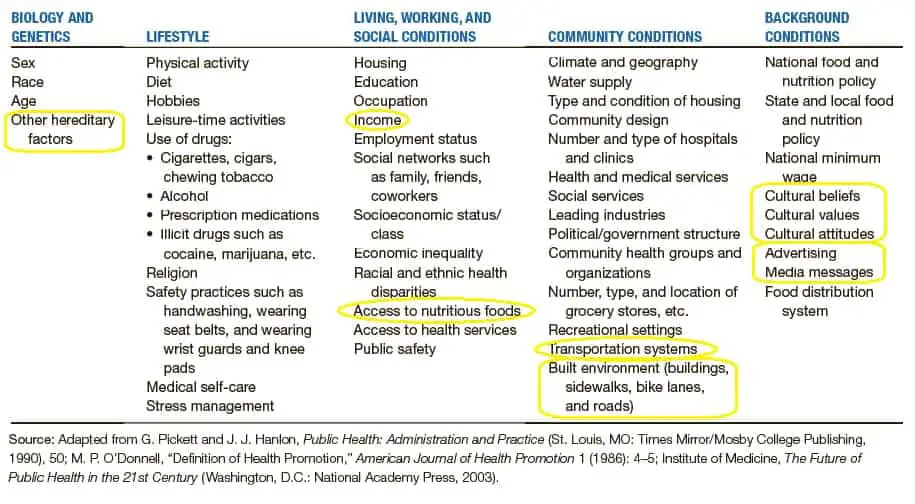

Anyway, what we’ll do here is go over the potential barriers to change for adopting a 100% plant-based diet using what are known as determinants of health.

The WHO calls the determinants of health, “the range of personal, social, economic, and environmental factors that influence health status are known as determinants of health.”8

They fall under several broad categories:

- Policymaking

- Individual behavior

- Social factors

- Physical factors

- Health services

- Biology and genetics

It’s the interrelationship among these six factors that determine individual and population health.

The public sector uses this type of information to develop health campaigns. I feel like it’s solid information, as it’s been used to radically reduce smoking and improve breastfeeding, etc.

Not all five are relevant for our purposes, but we’ll cover what is.

Those that are relevant to nutrition include:8,9

- Individual behavior. This relates to your diet and food preferences and is something everyone can relate to. Fortunately, this is also the area you exert the most control over.

- Social barriers. These are the social factors of the environment in which we’re born, live, learn, work, and age. They impact a wide range of health, quality-of-life, and functioning outcomes. They include social norms and attitudes, availability of resources, social support and interactions, SES conditions, poverty, personal transportation options, and mass media.

- Physical barriers. Like social determinants, physical determinants of health are the physical conditions in which we live. These include the food available at worksites and schools, public transportation, physical barriers (especially for those with disabilities).

- Biology and genetics. Relevant factors here would include autoimmune disorders, food allergies, and intolerances, digestive issues, etc.

Food Preferences

This is a big one because it’s something we all have to deal with. It may sound trivial compared to other factors, but giving up your favorite foods—foods you’ve enjoyed your entire life—is no small task.

Anyone who tells you otherwise has probably been vegan for so long that they forgot how good some of the animal-based products are. I’m always shocked to find hardcore vegans who say that they swear that a certain vegan replacement is just as good as the original and that they can’t tell the difference.

Thankfully, 100% plant-based diets are getting much easier in this respect, given the increasingly available plant-based versions of the most popular food items. But, no matter how good the alternatives get, I’d imagine everyone who goes vegan will likely end up with at least one all-time favorite food item that they just can’t seem to find a replacement for.

This is different for everyone. For me, I rarely miss eating meat, but I love, love, love mozzarella cheese. Pizza is my all-time favorite food. Unfortunately, I’ve yet to try a vegan cheese that closely resembles the original. At least for mozzarella.

Some of the other cheeses I’ve tasted come pretty close, but mozzarella replacements have been pretty disappointing. And I’ve tried them all.

I’ve found some of the newer realistic burgers to be really good—almost indistinguishable from real meat, in my opinion. But, like me and cheese, for some of you, that won’t be the case. Again, it’s different for everyone.

This issue also intersects with some of the others mentioned below, as people will have varying access to boutique products and plant-based alternatives. If you live in rural West Virginia, Walmart may be the closest thing to Trader Joes you can find.

Things will likely only get better in this area. I remember when vegan mayo was a super rare find, but just last week I ran across some at Target. If it’s hard, don’t worry about it. It’s normal. If someone tells you otherwise, keep in mind that the person likely didn’t have to give up many of their favorite foods.

Social Norms and Attitudes

This one has quite a big impact on many people. I for one hate telling people that I’m vegan. Is it because I’m ashamed? No, I just don’t feel like explaining it over and over and over again. It’s not serious by any means. It’s more annoying than anything.

If dealing with others’ reactions to your food choices is the biggest challenge you have on the vegan diet, then count yourself lucky. This is a good attitude to cultivate. Many of us are so fortunate to live in an era in which we can supplement synthetic vitamin D and B12.

Not only were we born in an era that allows us to access needed nutrition from non-animal-derived sources, but many of us are fortunate to live in a geographic region that allows ready access to healthy plant-based foods and animal-product alternatives.

So, if it comes with the small price tag of dealing with odd looks and soy jokes, I’d say that’s a pretty good deal.

Now, for some, it can go a bit beyond enduring the endless questions, looks, and comments. People who come from a culture with a rich tradition of eating certain animal products can find that their family doesn’t take well to their newfound eating habits.

One popular vegan Youtuber, Eisel Mazard recounts in a video the gut-wrenching experience of turning down his mother’s food. I’d post the video but can’t seem to find it.

I’ve been fortunate to have parents that don’t give me a hard time about diet and are actually very accommodating. But I realize that not everyone is that lucky. I remember one friend telling me that his family (from Turkey) thought that the vegan diet was an insult to his family’s heritage (not that that’s how people from Turkey typically think).

It also seems to matter more for younger people. A growing body of evidence suggests adolescents and young adults have similar dietary patterns as their peers.10-13

Some studies have shown social norms, and perceptions of peer behavior to potentially influence health behaviors, particularly in children, adolescents, and young adults.14-17

Most studies looking at the effects of social norms in middle adulthood (34-52 years in this case) have been focused on alcohol use.15,18-20

But, some studies have found social norms to be associated with several health behaviors, including the consumption of high energy-dense foods, fruits, and vegetables.21-24

So, it’s not a far leap to assume peer group to influence intake of animal vs. plant products. I can say from experience, that of the times I’ve felt an overwhelming urge to eat animal products, I was always around non-vegan friends and family. The feeling usually had less to do with overt peer-pressure and much more to do with convenience, and the normalizing of animal products you experience when around non-vegans. At least, in my experience.

Built Environment (Access to Healthy Food)

Source: Planh. https://planh.ca/news/available-planh-healthy-built-environment-linkages-toolkit-design-planning-health

In city planning, the “built environment” encompasses a range of community design elements like street layout, zoning, public transportation options, and business areas.25

For our purposes, access to produce—a mainstay of vegan diets—requires the availability of grocery stores, supermarkets, and farmers’ markets.

Researchers have found an association between lack of grocery stores in inner cities and obesity.26

Several studies indicated rural, minority, and poor neighborhoods

What this means is that folks who live in areas with few options for food shopping are more likely to eat an excess of calories. How is this possible? Because, they’re forced to over rely on convenience foods—foods high in energy density and low in nutrients.

When you get most of your meals from fast food restaurants and convenience stores you’re extremely limited in what you can eat and almost none of it is healthy. Imagine trying to eat a vegan diet in such circumstances.

These are called food deserts, defined by the USDA as “urban neighborhoods or rural towns without ready access to fresh, healthy, and affordable food.”30

According to the USDA’s Economic Research Service, low access to healthy food is defined as “being far from a supermarket, supercenter, or large grocery store (“supermarket” for short). A census tract is considered to have low access if a significant number or share of individuals in the tract is far from a supermarket.”31

There are several ways they measure this. For example, a tract is considered low acces if, “a significant number (at least 500 people) or share (at least 33 percent) of the population is greater than ½ mile from the nearest supermarket, supercenter, or large grocery store for an urban area or greater than 10 miles for a rural area.” 31

With this measure, an estimated 17.7% of the U.S. population, live in low-income tracts, have low access to healthy food, and are more than ½ mile (with no transportation) or 10 miles (with transportation) from the nearest supermarket. 31

In the US, some states are inflicted with this problem more than others. For example, in Mississippi, 70% of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) recipients live 30 or more miles away from the nearest large supermarket.30

Low availability is also associated with certain demographics. In Baltimore, researchers found supermarkets in majority black neighborhoods to have lower availability of healthy foods compared to supermarkets in predominantly white neighborhoods.

The problem seemed to go beyond the availability of stores, as the lower availability of healthy foods in black neighborhoods was due not only to the differential placement of types of stores (Walmart vs Whole Foods, etc.) but also to the differential offerings of healthy foods within the same stores.32

Financial Barriers

The problems of built environment overlap with financial barriers.

As mentioned above, neighborhoods that are poor have been shown to have less access to supermarkets and affordable healthy food choices.27-29

It’s estimated that over 29 million Americans lack access to affordable, healthy foods.30

So, not only is access to a variety of healthy food harder to come by, but it’s more expensive when you encounter it.

This has given rise to a phenomenon known as the paradox of obesity and poverty, wherein poverty is associated with excessive food energy intake. It turns out obesity rates tend to be higher in lower-income neighborhoods, states, and districts.33

Some experts (but not all) think the association may be due to lower costs of higher energy dense foods (dollars per megajoule). I.e the ability of socioeconomically disadvantaged groups to access and purchase high energy-dense foods may contribute to their higher rates of obesity.34-38

The relevance to plant-based diets is clear: 100% plant-based diets based on whole minimally processed foods are far from energy dense. Chains like Dollar General provide rural and inner-city households with cheap sources of concentrated energy from sugars, fat, and high-fat meats while offering little in the way of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains.

I can say from personal experience, that the vegan diet can tend to be a bit more expensive depending on the quality of the food. Sure, rice and beans are cheap, but fresh produce isn’t. Not to mention popular foods like ice cream. If you want to splurge on ice cream as a vegan, you’ll usually have to go for a boutique brand like Benn and Jerry’s as you won’t be able to just grab the nearest store brand or Mayfield.

Genetic Barriers: Food Intolerances

Unlike puzzled looks and annoying comments from friends, this one is quite serious. Eisel Mazard (the guy I discussed above) is one of the most hardcore vegans out there and pulls no punches when it comes to addressing common excuses for eating animal foods.39

Yet even he was sympathetic to a caller who was having to incorporate animal products into her diet due to having Crohn’s disease. The vegan diet is already very restrictive, and when you have digestive problems with many plant foods or have food intolerances that preclude you from eating one or more of the very few food groups you’re actually allowed to eat, it can be nigh impossible to get adequate nutrition.

At that point, you’re down to eating one or two foods for the rest of your life. Not doable. Not only is it impractical/difficult, but it would also likely lead to numerous nutritional deficiencies.

While digestive issues like Crohn’s and IBD are relatively uncommon, there are many other food intolerances that are widespread.

For example,

Having the wrong food intolerance can wipe out an entire food source that would otherwise be a staple in a 100% plant-base diet.

Information Barriers

The media is just loaded with conflicting dietary info. One day Dr. Oz is promoting the vegan diet as healthy, and the next he’s interviewing Jordan Peterson on the benefits of the carnivore diet, or pushing Ostrich burgers as the meat of the future.

There will always be “doctors” out there who will call into question the safety of plant-based diets. It doesn’t matter that every reputable health organization in the world (WHO, HHS, USDA, AND, etc.) endorses a vegan diet to be suitable for all stages of the life cycle.

There will always be the fringe doctors and experts who will try to persuade people to abandon their plant-based diet which obviously doesn’t help adherence.

The fact of the matter is, one of the main premises that people accept before adopting a 100% plant-based diet is that it’s at the very least healthy. Folks vary in the degree to which they believe vegan diets to be a miracle pill, but most, at the very least, believe the eating pattern to be healthy enough to follow long term without a net negative effect on health.

When health experts start calling that into question, it can cause all sorts of problems. If you’re sick or having a bad week for some reason, you’re ripe for the fringe doctor to come in with his pseudoscience and persuade you to jump ship.

That’s one reason I’ve created this site: to lower the barriers to becoming vegan by providing people with as much quality information as possible.

So, that does it for now. Perhaps, next, I’ll tackle

Until next time.

References

- Health.Usnews.Com, 2016. Best Weight-Loss Diets (Online). U.S. News & World Report L.P. Available from: http://health.usnews.com/best-diet/best-weight-loss-diets.

- Moore, J., Mcgrievy, M., Turner-Mcgrievy, G., 2015. Dietary adherance and acceptability of five different diets, including vegan and vegetarian diets, for weight loss: the new DIETs study. Eat. Behav. 19, 33–38.

- Huang, R.-Y., Huang, C.-C., Hu, F.B., Chavarro, J.E., 2015. Vegetarian diets and weight reduction: a metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 31, 109–116.

- Jenkins, D.J., Wong, J.M.W., Kendall, C.W.C., Esfahani, A., Ng, V.W.Y., Leong, T.C.K., Faulkner, D.A., Vidgen, E., Gregory, P., Mukherjea, R., Krul, E.S., Singer, W., 2014. Effects of a 6-month vegan low-carbohydrate (‘eco-Atkins’) diet on cardiovascular risk factors and body weight in hyperlipidaemic adults: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 4, e003505.

- Turner-Mcgrievy, G., Davidson, C.R., Wingard, E.E., Billings, D.L., 2014. Low glycemic index vegan or lowcalorie weight loss diets for women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a randomized controlled feasibility study. Nutr. Res. 34, 552–558.

- Glanz K. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory Research and Practice, 3rd Ed. San Francisco: Pfeiffer, 2002.

- Rosenstock, I. M. “The Health Belief Model and Preventive Health Behavior.” Health Education Monographs, 1974, 2(4), 354–386.

- Determinants Of Health https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/about/foundation-health-measures/Determinants-of-Health

- State of the Air [Internet]. Washington, DC: American Lung Association. Available from: http://www.stateoftheair.org

- Bruening M, Eisenberg M, MacLehose R, et al. Relationship between adolescents’ and their friends’ eating behaviors: breakfast, fruit, vegetable, whole-grain, and dairy intake. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(10):1608–1613.

- Ali MM, Amialchuk A, Heiland FW. Weight related behavior among adolescents: the role of peer effects. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e21179.

- Lau RR, Quadrel MJ, Hartman KA. Development and change of young adults’ preventive health beliefs and behavior: influence from parents and peers. J Health Soc Behav. 1990;31(3):240–259.

- Wouters EJ, Larsen JK, Kremers SP, et al. Peer influence on snacking behavior in adolescence. Appetite. 2010;55(1):11–17.

- Rimal RN. Modeling the relationship between descriptive norms and behaviors: a test and extension of the theory of normative social behavior (TNSB). Health Commun. 2008;23(2):103–116.

- Rimal RN, Real K. How behaviors are influenced by perceived norms: a test of the theory of normative social behavior. Communic Res. 2005;32(3):389–414.

- Baker CW, Little TD, Brownell KD. Predicting adolescent eating and activity behaviors: the role of social norms and personal agency. Health Psychol. 2003;22(2):189–198.

- Rivis A, Sheeran P. Descriptive norms as an additional predictor in the theory of planned behavior: a meta-analysis. Curr Psychol. 2003;22(3):218–233.

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Peer influences on college drinks: a review of the research. J Subst Abuse. 2001;13(4):391–424.

- Borsari B, Murphy JG, Barnett NP. Predictors of alcohol use during the first year of college: implications for prevention. Addict Behav. 2007;32(10):2062–2086.

- Woodyard CD, Hallam JS, Bentley JP. Drinking norms: predictors of misperceptions among college students. Am J Health Behav. 2013;37(1):14–24.

- Perkins JM, Perkins HW, Craig DW. Misperceptions of peer norms as a risk factor for sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among secondary school students. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(12):1916–1921.

- Lally P, Bartle N, Wardle J. Social norms and diet in adolescents. Appetite. 2011;57(3):623–627.

- Ball K, Jeffery RW, Abbott G, et al. Is healthy behavior contagious: associations of social norms with physical activity and healthy eating. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7(1):86–94.

- Croker H, Whitaker KL, Cooke L, Wardle J. Do social norms affect intended food choice? Prev Med. 2009;49(2-3):190–193

- Wendy Collins Perdue, JD, Lesley A. Stone, JD, and Lawrence O. Gostin, JD, LLD. The Built Environment and Its Relationship to the Public’s Health: The Legal Framework. Am J Public Health. 2003 September; 93(9): 1390–1394.

- Adam Drewnowski, Anju Aggarwal, Philip M. Hurvitz, et al. Obesity and Supermarket Access: Proximity or Price? Am J Public Health. 2012 August; 102(8): e74–e80.

- Kaufman P. Rural poor have less access to supermarkets, larger grocery stores. Rural Development Perspectives. 1998;13:19–26

- Linda K. Ko, Cassandra Enzler, Cynthia K. Perry, et al. Food availability and food access in rural agricultural communities: use of mixed methods. BMC Public Health. 2018; 18: 634.

- Angela Hilmers, David C. Hilmers, Jayna Dave. Neighborhood Disparities in Access to Healthy Foods and Their Effects on Environmental Justice. Am J Public Health. 2012 September; 102(9): 1644–1654.

- Boyle, Marie A. Community Nutrition in Action: An Entrepreneurial Approach (Page 291). Brooks Cole.

- Documentation. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-access-research-atlas/documentation/

- Franco M, Diez Roux AV, Glass TA, Caballero B, Brancati FL. Am J Prev Med. 2008 Dec; 35(6):561-7. Epub 2008 Oct 8.

- Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (mmwr). https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/wr/mm6650a1.htm

- Kristin A Evans, PhD, Drewnowski A The cost of US foods as related to their nutritive value. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:1181–1188.

- Lipsky LM. Are energy-dense foods really cheaper? Reexamining the relation between food price and energy density. Am J Clin Nutr.2009;90:1397–1401.

- Carlson A, Frazao E. Are healthy foods really more expensive? It depends on how you measure the price. USDA Economic Research Service; 2012. (Economic Information Bulletin 96).

- Todd JE, Leibtag E, Penberthy C. Geographic differences in the relative price of healthy foods. USDA Economic Research Service; 2011. (Economic Information Bulletic 78).

- Katz DL, Doughty K, Njike V, et al. A cost comparison of more and less nutritious food choices in US supermarkets. Public Health Nutr. 2011; 14: 1693–1699.

- Eisel Mazard Vs Flemface: Ethical Questions Within Veganism. à-bas-le-ciel – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y1X4uiUztgo

- Sicherer SH, Furlong TJ, Muñoz-Furlong A, Burks AW, Sampson HA. A voluntary registry for peanut and tree nut allergy: characteristics of the first 5149 registrants. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001; 108: 128–32.

- Bock SA, Atkins FM. Patterns of food hypersensitivity during sixteen years of double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenges. J Pediatr 1990; 117: 561–7.

- Hosking CS, Heine RG, Hill DJ. The Melbourne Milk Allergy Study: two decades of clinical research. Allergy Clin Immunol Int 2000; 12: 198–205.

- Burks AW, James JM, Hiegel A, Wilson G, Wheeler JG, Jones SM et al. Atopic dermatitis and food hypersensitivity reactions. J Pediatr 1998; 132: 132–6.

- Dalal I, Binson I, Reifen R et al. Food allergy is a matter of geography after all: sesame as a major cause of severe IgE-mediated food allergic reactions among infants and young children in Israel. Allergy 2002; 57: 362–5.

- Eigenmann PA, Calza AM. Diagnosis of IgE-mediated food allergy among Swiss children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2000; 11: 95–100.

- Host A, Halken S. A prospective study of cow milk allergy in Danish infants during the first 3 years of life: clinical course in relation to clinical and immunological type of hypersensitivity reaction. Allergy 1990; 45: 587–96.

- Sicherer SH, Munoz-Furlong A, Sampson HA. Prevalence of peanut and tree nut allergy in the United States determined by means of a random digit dial telephone survey: a 5-year follow-up study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003; 112: 1203–7.