A question I get all the time is whether or not the vegan diet offers any benefits when it comes to skin health and appearance. Of the most common skin-related inquiries are questions related to acne.

Is a whole food vegan diet uniquely beneficial in helping prevent or reverse acne? In short, it certainly can be. And throughout the article, I’ll be referencing studies to back up this claim. As I’ve mentioned before, the vegan diet offers many benefits, both by virtue of what it includes, and what it excludes from the diet. In the case of acne, the vegan diet really stands out from the rest by means of the latter.

Nearly every food known to cause or aggravate acne is of animal origin. Thus, by excluding all offending foods from your diet, you will stand the best chance of clearing up your skin once and for all.

It’s also important to note that, the weight of evidence—including the studies cited in this article—suggests that certain food choices play a role in aggravating acne, more so than being the root of the problem.1 One’s predisposition to acne is largely genetic, whereas diet and lifestyle help determine how the condition will manifest.There are a number of questions that remain to be addressed by additional research before the efficacy of a vegan diet for acne can be established 100%.

Even though the vegan diet won’t make you a 120-year-old in a 30-year-old body, it can definitely go a long way in helping you maintain a youthful appearance. One of the most commonly cited effects of people who switch to a vegan diet for any length of time is that their skin clears up and takes on a “glowing “appearance.

Now, like anything else, genetics plays a huge role in the appearance one’s skin but as I’ve touched on in previous articles, the environment—what’s called gene expression—is the other half of the equation.

Defining the Problem

The appearance of acne usually peaks during the adolescent years is estimated to affect between 80% and 90% of U.S. teens.2 Of course, the U.S. isn’t alone. After all, acne is known as a disease of western civilizaton.3

The problem doesn’t always end in adolescence. While it does tend to resolve following this period of life, 50.9% of women and 42.5% of men continue to suffer the effects of this disease well into their twenties.4

At age 40, 5% of women, and 1% of men still have acne lesions.5 As for the economic impacts, acne persists as the #1 cause of dermatology visits, with the average cost of care being estimated at $689.06 per patient per visit.6,7

Dismantling the Myths Around Acne

Myth 1 – It’s Only About Appearance

Some people think of concerns related aesthetics as a bit trivial, but treatment for this particular condition is extremely important because acne, if severe enough, can be absolutely debilitating.

For starters, it can significantly affect your quality of life overall, and it’s strongly linked to social withdrawal, depression, and anxiety.1

Because it primarily affects teens, the psychosocial component to the acne problem should be even more salient given the prevalence of depression in that demographic.

I don’t know about you, but when I was in my early teens I was easily embarrassed by everything. I never struggled with acne, but I can’t imagine that it would’ve made that period of my life any more pleasant.

Myth 2 – It’s All Genetics so There’s Nothing You Can Do

Another way in which people often dismiss the problem is by contributing it to genetics. However, research suggests the value of incorporating nutrition therapy into the treatment of acne can be as effective, if not more so, than pharmacological treatment.

A recent study of 250 young adults in New York, from ages 18 to 25, found evidence that dietary factors likely influence or aggravate the development of acne.2

Myth 3 – It’s an Age Thing. You Just Have to Ride It Out

Yet another limiting belief people have in regards to acne, is that nothing can be done about it because it’s an age thing. Because you’re young, you should expect to get acne, and you’ll just have to let it run its course.

However, this is not the case. In the above study of young adults, most were well past the age in which wild hormonal fluctuations would be playing a significant role.

Further, the young adults in the study with moderate to severe acne reported higher glycemic index diets, including loads of added sugars, servings of milk, and high intakes of saturated fat, and trans fatty acids.

As in higher levels than most young adults. Therefore, it’s quite possible that their worse-than-average diets played some role in their worse-than-average struggle with acne.

Additionally, most participants (58%) reported at least the perception that diet influence or aggravates their acne. I.e. when they had bouts of particularly bad eating patterns, it seemed as if their acne flared up to coincide with the terrible eating.

Brief Pathophysiology for Fellow Science Geeks

“Acne vulgaris” is a disease of what are known as pilosebaceous units (PSUs)—structures consisting of:

- A hair

- A hair follicle

- A small muscle called an erector pili

- A sebaceous gland—it secretes oil called sebum that protects your skin and keeps it nice and moisturized.

Popular Theories

Consensus of the exact mechanisms center around a few major processes, that happen separately and supposedly contribute to the condition:

Hyperkeratinization of the unit

There are cells that line the inside of the hair follicles. These cells function to detach or “slough off “ from the skin lining at regular intervals.

They can become disordered in a condition known as hyperkeratinization—where excess keratin (a protein) is produced which prevents the dead cells from leaving the follicle.

This disorder prevents the cells from detaching like they’re supposed to because the cohesion of cells blocks the hair follicle and clogs the sebaceous/oil duct leading to acne.

Sebum Production

Your skin pumps out too much sebum, creating an environment conducive to bacterial growth

Follicular Colonization and Activity of P Acnes

P acnes is an abundant bacterium on human skin, especially in sebaceous areas. It’s thought to be an opportunistic pathogen and is implicated in the development of a range of medical conditions.

Anyway, you don’t want this stuff accumulating in your pores.

Hormonal influence

The major growth hormone in puberty is insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1).8 Many researchers now believe that it’s IGF-1, not androgens that correlate with the manifestation of acne.9

According to Bodo M, “IGF-1 signaling is the central endocrine pathway of puberty and sexual maturation, and is the converging point of nutrient signaling in acne.”10 Insulin may also play a role.

Innate Immunity – A New Development

Recent research focuses on what’s known as “innate immunity.” In short, inflammation promotes acne via the activation of the innate immune system. With this new development, the list of proposed processes looks very similar to the above (and equally incomprehensible).

The main difference is that inflammation mediated by interleukin 1 (IL-1) precedes the hyperkeratinization process.10,11,12 The process involves a host of other mediators and enzymes that I won’t go into here—because I’m not that masochistic.

The main thing to take from this is that acne is caused, in part, by inflammation. Various nutrients play a role, for better or worse in the inflammatory processes.

For example, as touched on below, the dairy food group can be problematic for many people who struggle with acne. Dairy is implicated in the above process involving hyperkeratinization.

Specifically, dairy milk contains testosterone precursors that, upon conversion to dihydrotestosterone (DHT) via testosterone, stimulate the PSU.13,14,15 That’s right, androgens are of course involved in protein synthesis.

And as you know, keratin is a protein. Thus the implication of dairy in the process of hyperkeratinization.

Now that’s just one of many potential roles that dairy might play. But hopefully, this example will help make the above arbitrary sounding information seem slightly less arbitrary.

The Acne-Diet Connection, and the Benefits of the Vegan Diet

So, what’s all this have to do with the vegan diet? Well, all of the above processes affect each other and are linked in one way or another to diet.

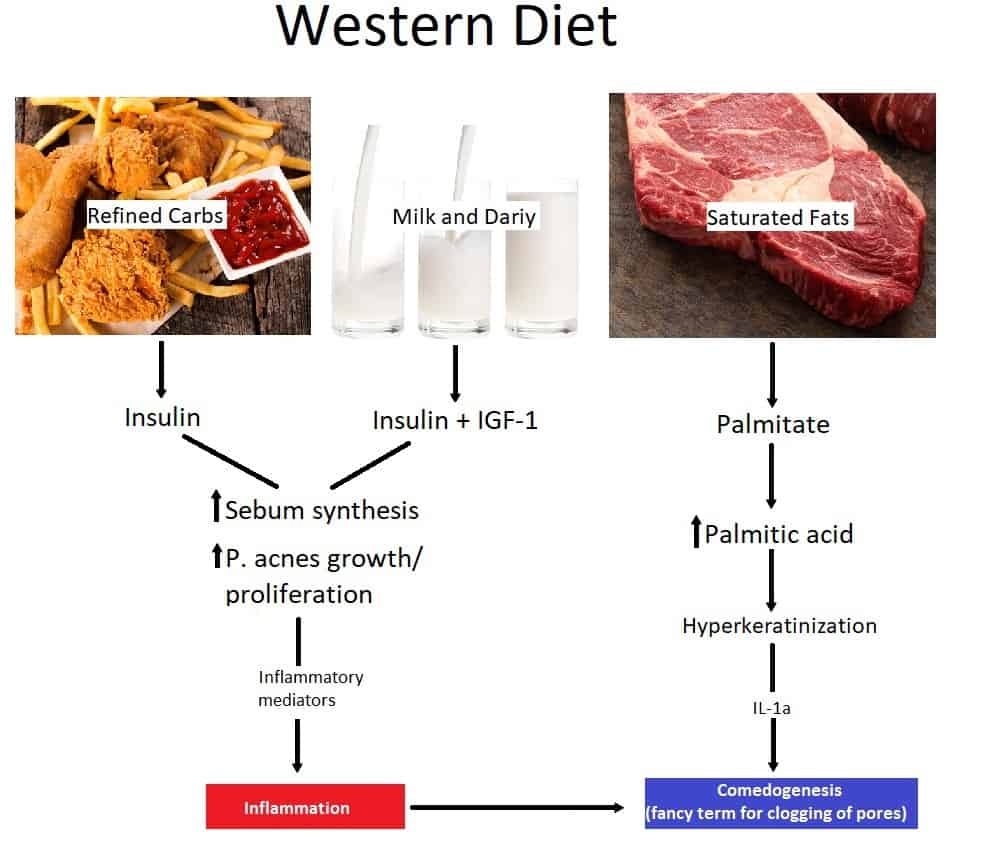

And as you can see from the chart, a whole-food vegan diet pretty much ticks all the boxes when it comes to eating for clear skin. The following is a much-

If you’re interested in the details that account for the relationship arrows, I highly suggest you visit the study linked in the reference.

What Eating Pattern Best Helps Achieve Clear Skin?

Now, this may seem slightly anticlimactic—all that info above just for a handful of guidelines. But the specifics are really pretty straight forward. The evidence base most consistently supports the efficacy of excluding and incorporating a few food choices.

You might be thinking, “could only a handful of dietary guidelines really tackle such a huge problem like acne?” But keep in mind that basically, no one eats this way. Not in industrialized countries. Acne isn’t known as a disease of western civilization for nothing.

What’s to be included?

- A diet low in saturated fat

- A diet high in whole grains, fruit, and vegetables

- Consumption of omega-3 fatty acids

What should be avoided?

- Eating a healthful, low-glycemic load diet16,17

- Of course, avoid any and all dairy products.17-19

Believe it or not, according to Reed M., et al. authors of The Dietitian’s Guide to Vegetarian Diets, chocolate, and greasy foods do not appear to affect acne.21

So they don’t make the list. Of course, as a site that promotes veganism, I suggest you stay away from milk chocolate in general.

Keep in mind that these are just general guidelines. Everyone is different, and there’s no replacement for paying attention to what affects you as an individual. It would probably be helpful to keep a food and symptom diary to identify problematic foods.

References

- Burris J, Rietkerk W, Woolf K: Acne: the role of medical nutrition therapy, J Acad Nutr Diet 113:416, 2013.

- Burris J, Rietkerk W, Woolf K: Relationships of self-reported dietary factors and perceived acne severity.

- Cordain L, Lindeberg S, Hurtado M, et al. Acne vulgaris: a disease of Western civilization. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138(12):1584-90.

- Collier CN, Harper JC, Cafardi JA, et al. The prevalence of acne in adults 20 years and older. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008; 58(1):56 59.

- Cunliffe WJ, Gould DJ. Prevalence of facial acne vulgaris in late adolescence and in adults. Br Med J 1979; 1(6171):1109 1110.

- Pawin H, Chivot M, Beylot C, et al. Living with acne. A study of adolescents’ personal experiences. Dermatology 2007; 215(4):308 314.

- Yentzer BA, Hick J, Reese EL, et al. Acne vulgaris in the United States: a descriptive epidemiology. Cutis 2010; 86(2):94 99.

- Juul A, Bang P, Hertel NT, et al. Serum insulin-like growth factor-I in 1030 healthy children, adolescents, and adults: relation to age, sex, stage of puberty, testicular size, and body mass index. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;78(3):744–752.

- Deplewski D, Rosenfield RL. Growth hormone and insulin-like growth factors have different effects on sebaceous cell growth and differentiation. Endocrinology. 1999;140(9):4089–4094.

- Bodo M, Linking diet to acne metabolomics, inflammation, and comedogenesis: an update. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:371–388. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4507494/#b10-ccid-8-37

- Guy R, Green MR, Kealey T. Modeling acne in vitro. J Invest Dermatol 1996;106:176 182.

- Downing DT, Stewart ME, Wertz PW, et al. Essential fatty acids and acne. J Am Acad Dermatol 1986; 14:221 225.

- Ingham E, Eady EA, Goodwin CE, et al. Pro inflammatory levels of interleukin 1 alpha like bioactivity are present in the majority of open comedones in acne vulgaris. J Invest Dermatol 1992; 98:895 901.

- Darling JA, Laing AH, Harkness RA. A survey of the steroids in cows’ milk. J Endocrinol 1974; 62:291 297.

- Adebamowo CA, Spiegelman D, Danby FW, et al. High school dietary dairy intake and teenage acne. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005; 52:207 214.

- Hartmann S, Lacorn M, Steinhart H. Natural occurrence of steroid hormones in food. Food Chem 1998; 62:7 20.

- Smith RN, Mann NJ, Braue A, et al. A low-glycemic-load diet imroves symptoms in acne vulgaris patients: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:107-115.

- Danby FW. Diet and acne. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26(1):93-96.

- Adebamowo CA, Spiegelman D, Berkey CS, et al. Milk consumption and acne in teenage boys. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(5):787-793.

- Adebamowo CA, Spiegelman D, Berkey CS, et al. Milk consumption and acne in adolescent girls. Derm online J. 2006;12(4):1.

- Mangels R, Messina V, Messina M. The Dietitian’s Guide to Vegetarian Diets: Issues and Applications. Jones & Bartlett Learning, 3 ed. 2010.