If you’ve been researching the topic of plant-based diets for any length of time, you’ve probably run into common terms such as vegan, vegetarian, and perhaps even some monstrosities such as “lacto-ovo-pesco-macro-tarian”…

Okay, I’ll admit I made the last one up. If you’re feeling overwhelmed by the sea of information out there, you’ve come to the right place, because I am about to clear things up once and for all.

For Starters, What Is a Plant-Based Diet?

Well, there are two answers to this question…

An Umbrella Term for Diets Centered on Whole Plant Foods

Plant-based diets are centered around the consumption of minimally processed vegetables, fruits, legumes, whole grains, nuts and seeds, herbs, and spices. For the most part, it excludes animal products, including poultry, red meat, fish, dairy and eggs.1

So, in this sense, the designation “plant-based” is used simply as a superordinate term for the entire gamut of diets centered around the consumption of whole, plant foods.

Within this category of eating patterns exists a spectrum of diets that vary in the degree of the restriction of food choices—typically of animal foods, though some variations such as the macrobiotic diet (not covered here) restrict the types of plant foods allowed.

A Synonym for Flexitarianism

Another sense in which the term “plant-based” is used is as a synonym for what’s colloquially known as “flexitarianism”—what you might think of as the weekend warriors of plant-based eating patterns.

Many omnivores eat a plant-based diet, consuming meat, dairy, and eggs while emphasizing plant foods in their meals. This is usually done for health reasons, but adherents may also cite concerns for animal welfare and/or reducing their carbon footprint, etc.

Thus, of all the subgroups of plant-based dieters, flexitarians tend to be the least ideological as a whole, largely adhering to the eating pattern for the purpose of good health.

In this vein, you may have heard of the public health awareness campaign known as Meatless Monday, which advocates that Americans consume a vegetarian meal at minimum once per week in order to help reduce the incidence of chronic conditions/diseases (obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, etc.).2

Vegetarian Diet Patterns

True vegetarianism, in its least restrictive form, simply requires the elimination of meat and poultry, while allowing other animal products.

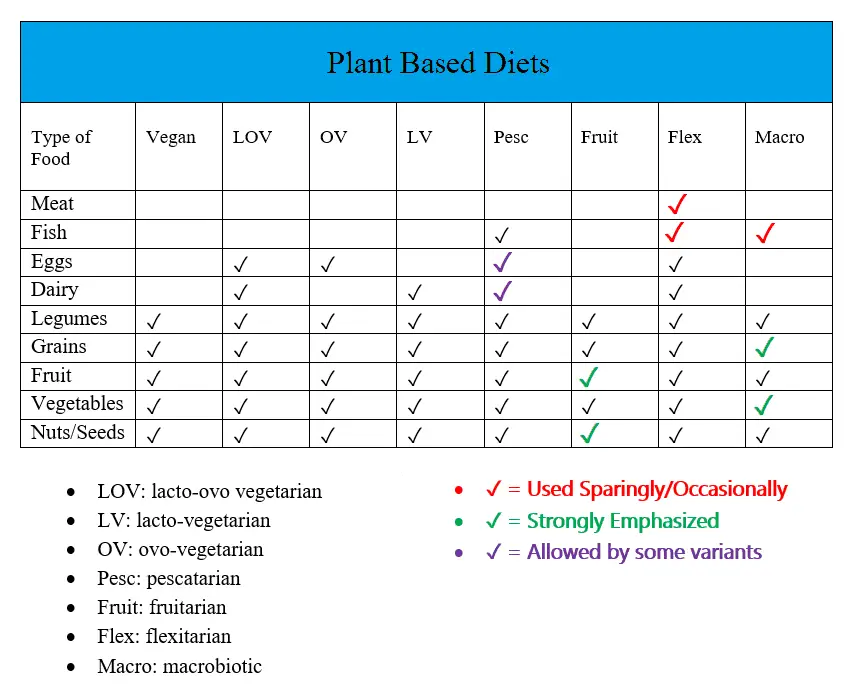

Here’s a chart if you’re in a big rush. It will help you sort out the differences between the various plant-based diets. It distinguishes the different categories based on foods consumed/avoided.

It’s comprehensive, and thus huge, so you may have to zoom in a bit if you’re on mobile.

Now, w’ll get into the details of how the above chart came about.

Lacto-ovo-vegetarians (dairy + eggs + plants)

Approximately 90 to 95% of vegetarians in North America incorporate dairy and/or eggs in their diets to some degree.3

This group allows for dairy products, but also consume eggs. This is a version of vegetarianism often practiced by Seventh-day Adventist (SDAs) and has been popular with this population going on 130 years.4

Hinduism is also associated with this way of eating. Many are either raised as lacto-vegetarians or lacto-ovo-vegetarians.5

Lacto-vegetarians (dairy + plants)

They don’t eat meat, poultry, fish, or eggs, but do consume milk, cheese, and other dairy products. Jainism is most associated with lacto-vegetarianism. Jainism prohibits its adherents from causing harm to anything thought to have a soul. Eggs are thought to have a soul, thus only dairy makes the cut.32

Ovo-vegetarians

Eggs + plants.

Vegans

On the other end of the plant-based eating spectrum, opposite flexitarians, are vegans. A vegan does not consume any food of animal origin.

Being the most restrictive variant, it simultaneously offers the most potential health benefits, while also running the highest risk of causing nutrient deficiencies—the latter if done incorrectly. Notice I stress the word “if”.

According to the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, the world’s foremost authority on nutrition, “well-planned vegetarian diets are appropriate for individuals during all stages of the life cycle, including pregnancy, lactation, infancy, childhood, and adolescence, and for athletes.”6

For this reason, it is highly recommended that one follow a well-planned vegan diet to maximize health benefits while eliminating the risk of nutrient deficiency.

In contrast to flexitarians and even vegetarians, vegans—though some are primarily interested in health and wellness—are characterized by a serious concern regarding the ethics surrounding the consumption and use of animal products.

To them, the word vegetarian holds very little ethical significance. They often stand out, even from strict vegetarians, by their refusal to consume honey or wear leather or fur.

The most devout vegans may disagree on a range of controversial issues regarding the relationship of humans to animals (such as animal ownership, etc.), but most share a desire to live a life as free of animal exploitation as possible.

What’s with the Overlapping Definitions?

Hmmm, the definition of plant-based eating seems awful close to the definition of flexitarian eating.

Take for example the following definitions:

On Plant-Based Diets

“A plant-based diet is not necessarily a vegetarian diet”, as “many people on plant-based diets continue to use meat products and/or fish but in smaller quantities.7

On Flexitarian Diets

A flexitarian or semi-vegetarian diet is a diet that’s plant-based with the occasional inclusion of meat.8-11

Why the superfluous term? Well, I’m not 100% certain by far, and I don’t think anyone is. But, if I had to guess, I think the introduction of this term was more of a public relations move. See flexitarianism is derived from vegetarianism, which is a term that has many connotations, some religious or at least ideological.

I think the term plant-based is a way of moving away from those associations. It has much more of a secular vibe to it. And while people who adopt it are often motivated at least in part by ethical concerns regarding animal welfare, this term is more associated with health and wellness, sustainability and the like.

A Few Oddballs

Macrobiotic Diet

An eating pattern first popularized in Japan. For the most part, it’s a vegetarian diet that emphasizes grains and local vegetables. Its adherents try to avoid highly processed foods, refined food products, and most animal products.

The macrobiotic diet is often categorized as a variation of the vegan diet. This may be due to the fact that much of the concern around nutrient deficiency risk on vegetarian diets have been focused on restrictive eating regimens, namely macrobiotic and vegan diets.12

However, the macrobiotic diet is hardly vegan. This eating regimen is largely spiritual in nature. Additionally, it’s not uncommon for its adherents to consume some lean fish and meat from time to time.

This is a pretty important thing to note, because many of the studies of vegetarian health outcomes (specifically among children) published over the last thirty years or so, dealt mainly with folks following a macrobiotic diet.13-19

Fruitarian Diet

A diet characterized by the consumption of fruits, nuts and seeds, and legumes in some cases. This diet pattern has folks focus on procuring food in a way that doesn’t kill the plant of origin. Steve Jobs is perhaps the most notable modern day example of a once fruitarian. He followed the diet for a time in his early years.20

For this reason, it includes a few plants we don’t typically think of as fruit. In practice, it consists of fruits (fresh and dried), nuts, seeds, and selected vegetables.

Why the focus on not killing the plant of origin? There are many motivations that account for this way of eating, but I’ll name a couple here.

For one, this diet is associated with Jainism: the least violent religion/ideology to ever exist. Unlike ethical vegans, their concern for welfare extends to all living things including plants.21

For other fruitarians, the motivation to consume fruit hearkens back to an era in which humans were supposedly only gatherers.22

Pescatarian Diet (Pesco Vegetarian Diet)

A diet characterized by the exclusion of all meat except fish. However, some variants include eggs or dairy products.

One motivation for eating this way is that while a person may sympathize with the plight of strict vegetarianism and veganism, they’re hesitant to dive right in. They’re not sure how their body will respond to sudden restriction, or whether they’ll be getting adequate nutrition from the more strict variants of vegetarianism.23

Perhaps they don’t want to give up all animal flesh, so they opt to consume animals with lesser nervous systems—animals perhaps having less of a capacity to feel physical and emotional pain.

Others may plan to continue eating fish long term, as they believe that humans are meant to eat at least some meat in order to obtain nutrients not found in plants.

And for similar reasons (fish being potentially less sentient compared to higher animals), they opt to follow what they consider to be the most ethical version of vegetarianism that can be maintained long-term. I should note I’m not endorsing this line of reasoning, but merely describing it.24

The above are just a couple of potential motivations. I’m sure there are many motivations, some pertaining to religion, fasting, etc.

Relative Health Benefits of the Plant-Based Diets

As mentioned above, substantial evidence attests to the health benefits of plant-based diets in general, with the vegan diet offering the most potential benefits when done correctly.

Vegetarian Diets

For starters, studies conducted on Seventh-Day Adventists (SDA), a vegetarian population, indicate a reduction in rates of metabolic syndrome.25 This is very impressive considering the typical intake of individuals in the SDA community can be quite variable.

Despite the huge variation in diet quality among vegetarians, evidence from a few studies examining religious groups demonstrates that following a vegetarian diet confers several health benefits—specifically related to cancer, obesity, and cardiovascular disease risk factors.26

Specifically, there have been studies of Eastern Orthodox Christians and Seventh-day Adventists that have shown health improvements from vegetarian eating patterns in these populations.27,28,33

Vegan Diets

The vegan diet offers many benefits for a wide range of health parameters, and there are already some studies suggesting it leads to better health outcomes in the area of common chronic diseases. And this is despite its widespread adoption being a fairly recent phenomenon.

Here I’ll just touch on two of the most common conditions: cardiovascular disease, obesity, and cancer.

Vegans and Heart Disease

Where the vegan diet really shines is in the area of heart health. According to ongoing research, the vegan diet is the only eating pattern shown to be able to actually reverse atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).29

This is no surprise. After all, plant-based diets, in general, have long been associated with a number of health benefits, including lower cholesterol levels, blood pressure levels, and lower risk of heart disease, hypertension and type 2 diabetes, and cancer rates.

The nutritional profile of plant-based diets may explain some of the health advantages just mentioned. Whole food plant-based diets tend to be lower in dietary cholesterol, saturated fat, and have higher levels of beneficial nutrients such as dietary fiber, potassium, magnesium, vitamins C and E, carotenoids, folate, flavonoids, and other antioxidants and phytochemicals.

Vegans and Body Composition

As for body composition, vegetarians tend to have a lower body mass index (BMI), with vegans having the lowest BMI on average than any other population.30

Vegans and Cancer

There are a few reports from UK cohorts and from an Adventist Health Study (AHS 2). These reports included the relative risks for all types of cancers in various vegetarian subgroups and meat eaters.

After, they compared the relative risk between the different populations. The vegetarian group beat out the meat-eating group, suggesting that risk (for all cancers combined) may be as much as 10% lower in the vegetarian group, and nearly 20% lower in the vegan subgroup as compared to the meat-eating group.31

Anyway, hopefully, I managed to help clear up some of the confusion around definitions and terminology. I want you to know the difference so that you can consider the merits of each variant of the plant-based diets.

References

- Robert J Ostfeld, Definition of a plant-based diet and overview of this special issue. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2017;14(5):315. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5466934/

- Campaign Aims To Make Meatless Mondays Hip Allison Aubrey – https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=129025298

- Melina V., Davis B., Harrison V. Becoming Vegetarian , Book Publishing Co., Summertown, TN, 1995, 2.

- “A Position Statement on The Vegetarian Diet Adapted from the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists Nutrition Council”

- Surveys studying food habits of Indians include: “Dairy and poultry sector growth in India”

- Mallonee LFH et al: Position Paper of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Vegetarian Diets, J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:1266-1282.

- Summerfield, Liane M. (2012-08-08). Nutrition, Exercise, and Behavior: An Integrated Approach to Weight Management (2nd ed.). Cengage Learning. pp. 181–182. ISBN 9780840069245. A plant-based diet is not necessarily a vegetarian diet. Many people on plant-based diets continue to use meat products and/or fish but in smaller quantities.

- Langley-Evans, Simon. Nutrition: A Lifespan Approach. Wiley. p. 172.

- “Becoming a Vegetarian”. Kidshealth.org. Retrieved 2015-05-02.

- “Semi-Vegetarian – Vegetarianism”. Medicine Online. semi-vegetarian: mostly follows a vegetarian diet but eats meat, poultry and fish occasionally

- Koletzko, Berthold. Pediatric Nutrition in Practice. Karger. p. 130

- Jacobs, C. and Dwyer, J. T. Vegetarian children: appropriate and inappropriate diets. Am. J. Clin. Nutr., 48: 811, 1988.

- Shull, M. W., Reed, R. B., Valadian, I., et al. Velocities of growth in vegetarian preschool children. Pediatrics, 60: 410, 1977. 7.

- Dwyer, J. T., Palombo, R., Thorne, H., et al. Preschoolers on alternate life-style diet. J. Am. Diet. Assoc., 72: 264, 1978.

- Dwyer, J., Andrew, E. M., Valadian, I., et al. Size, obesity, and leanness in vegetarian preschool children. J. Am. Diet. Assoc., 77: 434, 1980.

- Dwyer, J. T., Dietz, W. H., Andrews, E. M., et al. Nutritional status of vegetarian children. Am. J. Clin. Nutr., 35: 204, 1982.

- Dwyer, J. T., Andrews, E. M., Berkey, C., et al. Growth in new vegetarian preschool children using the Jenss-Bayley curve fitting technique. Am. J. Clin. Nutr., 37: 815, 1983.

- van Staveren, W. A., Dhuyvetter, J. H. M., Bons, A., Zeelen, et al. Food consumption and height/weight status of Dutch preschool children on alternative diets. J. Am. Diet. Assoc., 85: 1579, 1985.

- van Staveren, W. A., and Dagnelie, P. C. Food consumption, growth, and development of Dutch children fed on alternative diets. Am. J. Clin. Nutr., 48: 819, 1988.

- “Steve Jobs” by Walter Isaacson. “Finally Jobs proposed Apple Computer. ‘I was on one of my fruitarian diets,’ [Jobs] explained.” p. 120. “She just wanted him to be healthy, and [Jobs] would be making weird pronouncements like, ‘I’m a fruitarian and I will only eat leaves picked by virgins in the moonlight.'” p. 68.

- Flügel, Peter (2002), “Terapanth Śvētāmbara Jain Tradition”, in Melton, J.G.; Baumann, G., Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices, ABC-CLIO

- Dundas, Paul (2002) [1992], The Jains (Second ed.), London and New York: Routledge

- Ronald L. Sandler, Food Ethics: The Basics, Routledge, 2014, p. 74.

- Rohrer, Finlo (5 November 2009). “The rise of the non-veggie vegetarian”. BBC News. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- Rizzo NS et al: Vegetarian dietary patterns are associated with a lower risk of metabolic syndrome: The Adventist Health Study 2, Diabetes Care 34:1225, 2013.

- Le, L.T., Sabaté, J., 2014. Beyond meatless, the health effects of vegan diets: findings from the adventist cohorts. Nutrients 6 (6), 2131–2147.

- Sabaté, J., Wien, M., 2010. Vegetarian diets and childhood obesity prevention. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 91 (5), 1525S–1529S.

- Lazarou, C., Matalas, A., 2010. A critical review of current evidence, perspectives and research implications of diet-related traditions of the Eastern Christian Orthodox Church on dietary intakes and health consequences. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/09637481003769782.

- Esselstyn C, Golubic M: The nutritional reversal of cardiovascular disease – Fact or fiction? Three case reports, Cardiology 20:1901, 2014.

- Serena Tonstad, et al. Type of Vegetarian Diet, Body Weight, and Prevalence of Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(5):791–796. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2671114/

- Timoth J Key, et al. Cancer incidence in vegetarians: results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC-Oxford). The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Volume 89, Issue 5, 1 May 2009, Pages 1620S–1626S, https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2009.26736M

- “Jainpedia”. Archived from the original on 2017-05-24. Retrieved 2017-05-24.

- Sarri, K.O., Tzanakis, N.E., Linardakis, M.K., Mamalakis, G.D., Kafatos, A.G., 2003. Effects of Greek Orthodox Christian Church fasting on serum lipids and obesity. BMC Public Health 3, 16. http:// dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-3-16.