This can get confusing as there are two types of vitamin D (check out the article here)—vitamins D2 (ergocalciferol) and D3 (cholecalciferol) both of which can be found in food and supplements.

Vitamin D2 is always vegan. Vitamin D3 occurring naturally in food never is. Vitamin D3 in supplements and fortified foods is rarely vegan, as it’s usually obtained from wool fat. To know for sure, you will have to reach out to the manufacturer, or look for products bearing the vegan label.1

Whether a certain source of vitamin D3 qualifies as vegan depends on how it is synthesized. Unfortunately, the synthesis of much of the vitamin D used in supplements and fortified foods relies on 7-dehydrocholesterol (the precursor) derived from sheep oil.

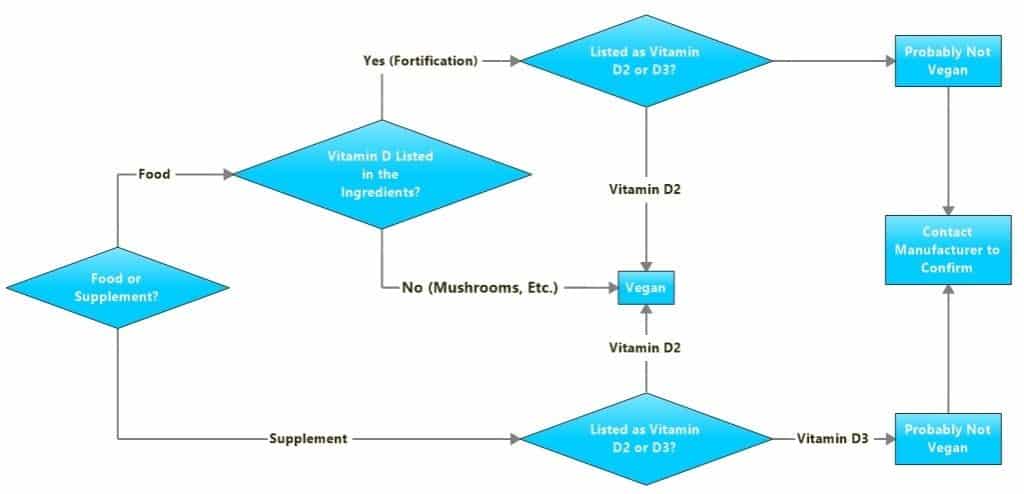

To have a better idea of whether your vitamin D is vegan-friendly, you’ll want to continue reading. For those who are in a rush, have a look at the flowchart here:

I should that it assumes you’re not using animal products.

Where Do Supplemental Vitamins Come from in General?

Extraction

Up until a few decades ago most vitamins added to supplements, fortified foods, and cosmetic products were industrially prepared using extraction technologies. Manufacturers would find extracts or concentrates in natural vitamin-rich staple food products.

In recent times the rise of new technologies for synthesizing these compounds made it less economically feasible to keep deriving the vitamins from their natural sources.

Reasons for opting to synthesize vitamins instead of extracting them include:2

- The synthetic processes are much cheaper

- The relative scarcity of vitamins in natural sources. The levels of vitamins found in natural plant and animal sources can fluctuate quite a bit—vitamin D in fish oil is an exception.

- The “organoleptic” (fancy word for taste, smell, etc.) properties of crude sources of vitamins can be undesirable.

- Shelf-life is less than optimal.

- The ease in which water-soluble vitamins tend to be lost by aqueous extraction

- Many of the molecules are “labile” (unstable), so many lend themselves to damage in the process of harvesting, preserving, and storing them.

So, these drawbacks eventually led industrial manufacturers to opt for the route of chemical and microbial synthesis.

Chemical Synthesis

Nowadays, many vitamins are made chemically, including: 2

- Pro‐vitamin A (carotenoids)

- Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol)

- Vitamin E

- Vitamin K1 (phylloquinone)

- Vitamin B1 (thiamine)

- Vitamin B5 (pantothenic acid)

- Vitamin B6

- Vitamin B7 (Biotin)

- Vitamin B9 (Folate)

Newer Methods

For other vitamins, several other methods have emerged, however, including enzymatic, microbial, and biotechnological methods.3-5

While capable of producing the above compounds, these methods have yet to prove profitable.

Examples of vitamins/vitamin-like compounds made exclusively via microbial fermentation (bacteria, fungi, and yeast) include:2

- Vitamin B2 (riboflavin)

- Vitamin C

- Vitamin B12

- Vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol)

- Vitamin K2 (menaquinone)

- Coenzyme Q10 (ubiquinone)

- Pyrroloquinoline quinine (PQQ)

Non-Vegan Vitamin D

Lanolin (Chemical Synthesis)

This is the type of vitamin D3 that’s likely in your favorite cereal. It’s the kind that’s added to orange juice and other commonly consumed staple food products.

Lanolin, also called wool grease, is a wax that’s secreted by the sebaceous glands of wooled animals. It’s referred to as wool fat/oil, but it’s not a true fat as it actually lacks glycerides.6-8

Its properties make it a good water-proofing agent and it helps sheep shed water from their coats. Certain breeds of sheep produce large amounts of lanolin.

The stuff is of interest to supplement manufacturers as it contains 7-dehydrocholesterol needed to synthesize vitamin D3 by irradiation with ultraviolet light.9

The type of lanolin produced and used by humans comes from domestic sheep breeds that are raised for their wool. So, if you’re a vegan for ethical reasons, you’ll want to steer clear as it’s definitely not appropriate for strict vegans.

Vegan Vitamin D

Vitamin D2

Mushrooms (Naturally Occurring)

Sunlight and UV-exposed mushrooms are an excellent source of vitamin D as they contain high amounts of the vitamin D precursor, provitamin D2.

When exposed to UV radiation, the provitamin D2 is converted to previtamin D2 at which point it rapidly converts to vitamin D2. The process is similar to how previtamin D3 converts to vitamin D3 in human skin.

D2 Supplements and Fortified Foods

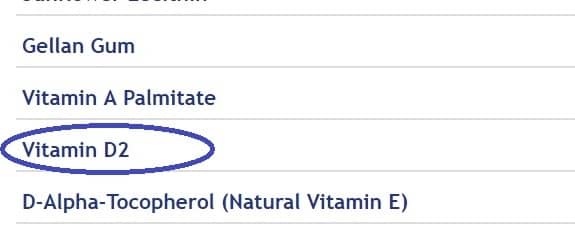

Many plant milks and vegan/vegetarian-friendly vitamin companies use vitamin D as D2. This will depend on the manufacturer, so you will have to check the label.

Look for the “vitamin D2” and/or “ergocalciferol” in the ingredients list, or clearly stated labels (Vegan Vitamin D, etc.)

Vitamin D3 (Extraction)

I’d mentioned extraction as an old method of manufacturing vitamin supplements and acquiring vitamins for fortified/enriched foods. Well, lichen is an exception.

Lichen is an organism arising from cyanobacteria or algae living among filaments of fungi species in a reciprocal relationship.10-12

Sound appetizing? But, seriously this stuff is pretty innovative. It turns out that there are edible forms of lichen that grow on trees and rocks in locations throughout North America, Scandinavia, and Asia.

Tips for Ensuring Your Vitamin D Is Vegan-Friendly

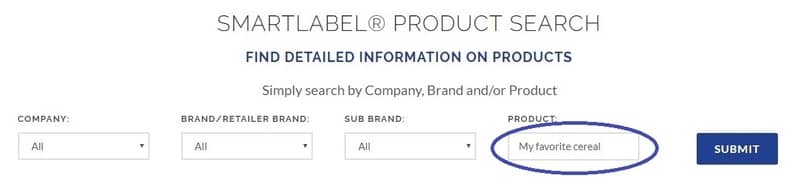

Check with SmartLabel (Resource)

SmartLabel is an organization dedicated to transparency when it comes to the ingredients used in food products.

Go to their product search page http://smartlabel.org/products. When you arrive at the website, simply type in the food product you’re looking for.

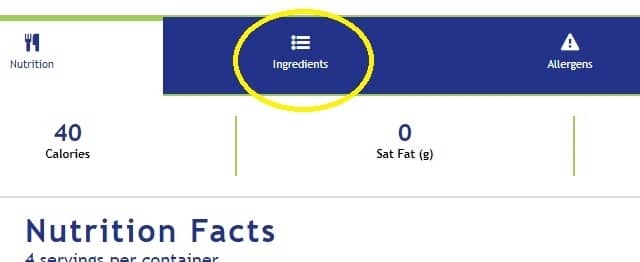

Locate and select the product, then select the ingredients tab.

Now just scroll down to where vitamin D is listed and it usually the type of vitamin D used. Of the many times I’ve used this service, it only once failed to list the type of vitamin D used.

Go with Certified Vegan Supplements

I’m not plugging any here, but a quick search will render you several supplement brands that are certified vegan. If a supplement has vegan D3, it won’t be hard to know as they’ll have it plastered all over the bottle. This lichen D3 is fairly new and companies are excited to advertise it.

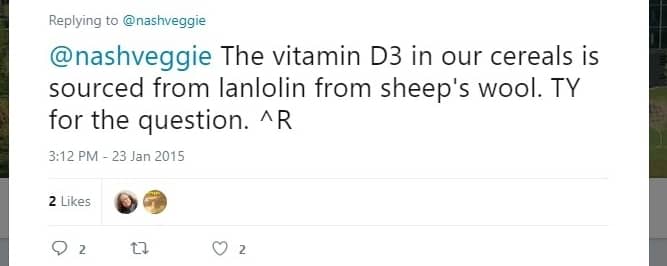

Reach out to the Manufacturer

If you can track down a number or an email address to a food manufacturer, they will often tell you how they source their ingredients. You can even ask them over social media. If you want to know which of your favorite cereals or juices have animal-sourced vitamin D3, look no further than Twitter.

Make Your Own

Depending on the time of year and where you live this can be easier said than done. But it’s still a reliable way to get vitamin D no matter what boutique vegan products you may or may not have available.

In the US, it’s thought that about 1.5 IU and 6 IU of vitamin D/cm2/hour can be synthesized by the skin during the winter and summer, respectively.13

With full body exposure to the sun, it’s estimated that, at least for fair-skinned individuals, about 10,000 to 20,000 IU vitamin D can be generated in 15 to 30 minutes.14

It’s thought that sufficient amounts of vitamin D can be obtainable by exposure to sunlight for around 5 to 15 minutes between the hours of 10 a.m. and 3 p.m. throughout the spring, summer, and fall.15

Stick with Vitamin D2

Vitamins D2 and D3 differ in structure (the side chains specifically) but are the same in their general metabolism and functions in the body.16

Many people have concerns about using D2 exclusively to meet vitamin D needs. In the body, vitamin D2 is metabolized to calcitriol by the same enzymes (25-hydroxylase and 1-hydroxylase) as vitamin D3. However, its metabolism generates additional byproducts not produced by D3 and it’s been suggested that it may be less efficient in producing calcitriol compared to D3.16

There are no long-term studies on folks who derived 100% of their vitamin D intake from vitamin D2.

But, as of now, it is endorsed by the various government health organizations to meet vitamin D needs. Overall, it’s just less commonly consumed and thus is often overlooked as a means of getting vitamin D.

References

- Dietary Supplements Pamela Mason – Pharmaceutical Press – 2007 (Page 339).

- Jose L. Revuelta, Ruben M. Buey, Rodrigo Ledesma‐Amaro, and Erick J. Microbial biotechnology for the synthesis of (pro)vitamins, biopigments and antioxidants: challenges and opportunities. Microb Biotechnol. 2016 Sep; 9(5): 564–567.

- Demain A.L. (2000) Small bugs, big business: the economic power of the microbe. Biotechnol Adv 18: 499–514.

- Demain A.L. (2007) The business of biotechnology. Ind Biotechnol 3: 269–283.

- Laudert D., and Hohmann H.‐P. (2011) Application of enzymes and microbes for the industrial production of vitamins and vitamin–like compounds In Comprehensive Biotechnology, 2nd edn, Vol. 3, Moo‐Young M., editor. (ed). Amsterdam: Elsevier B.V, pp. 583–602.

- Hoppe, Udo, ed. (1999). The Lanolin Book. Hamburg: Beiersdorf.

- Barnett, G. (1986). “Lanolin and Derivatives”. Cosmetics & Toiletries. 101: 21–44. ISSN 0361-4387.

- Riemenschneider, W.; Bolt, H. M., “Esters, Organic”, Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Weinheim: Wiley-VCH.

- Holick, M. F (2007). “Vitamin D deficiency”. New England Journal of Medicine. 357 (3): 266–81.

- “What is a lichen?”. Australian National Botanic Gardens. Retrieved 10 October 2014

- Introduction to Lichens – An Alliance between Kingdoms. University of California Museum of Paleontology.

- Brodo, Irwin M. and Duran Sharnoff, Sylvia (2001) Lichens of North America.

- Collins E, Norman A. Vitamin D. In: Rucker RB, Suttie JW, McCormick DB, Machlin LJ, eds. Handbook of Vitamins. 3rd ed. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc. 2001 pp. 51–114.

- Institute of Medicine, Food and Nutrition Board. Dietary Reference intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. 2011.

- Holick M. The vitamin D epidemic and its health consequences. J Nutr. 2005; 135:S2739–48.

- Gropper, Sareen S.; Smith, Jack L.. Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism (Page 394).