Believe it or not, one of the first articles I wrote was on the subject of the vegan diet and hemorrhoids (check out the article here). This article will be very similar, as constipation and hemorrhoids share much of the same etiology, and thus have the same relationship to plant-based eating.

However, they are two distinct conditions, so I decided to write an article focusing on constipation. After all, most people who suffer constipation probably wouldn’t think to read an article on hemorrhoids.

Does the Vegan Diet Cause Constipation?

No, not characteristically. In fact, quite the opposite. According to Messina, et al. authors of The Dietitian’s Guide to Vegetarian Diets, “Because vegetarians consume 50-100% more fiber than meat eaters, they are less likely to suffer from either constipation or hemorrhoids.”1

In comparing the stool frequency amongst omnivores, vegetarians, and vegans, Davies et al. stated “vegans, however, had a greater frequency of defecation and passed softer stools.”2

As you’ll see in the coming paragraphs, there are both ways in which a plant-based diet can help prevent and ways in which it can lead to constipation depending on its implementation.

Quick note: one thing I often get asked is whether there are any plant-based “superfoods” that are thought to help prevent constipation.

Aside from fiber, there’s been very little research in the area how specific foods affect stool outcomes. Sure, there are certain phytochemical-rich foods that are thought to help with stool frequency.

For instance, tamarinds have a fairly good track records in helping alleviate constipation.23

The Wolof people of Senegal have long used the fruit to prepare natural laxatives by mixing it with lime, honey, etc.24 Obviously, as a vegan, you’ll want to skip the honey. In Nigeria, rural Fulani consume soaked fruits to relieve constipation.25

But, again, there’s very little research supporting the efficacy of such protocols. So, when it comes to specific foods, those high in fiber–specifically insoluble fiber–come with the biggest endorsement.

Anyway, before we can really understand the ways in which the vegan diet can lead to certain stool-frequency outcomes, we first need to cover a few of the basics.

What Exactly Is Constipation?

This is a quick primer, and if you’re in a rush, you may want to skip down to the sections covering the ways in which the vegan diet can help prevent and/or lead to constipation.

The info in this section isn’t absolutely necessary, but may help you understand the interplay between plant-based diets and constipation.

Anyway, constipation is the condition of having fewer bowel movements than usual. It’s characterized by hard stool, excessive straining bowel movements, painful bowel movements, and incomplete emptying of the bowel.3

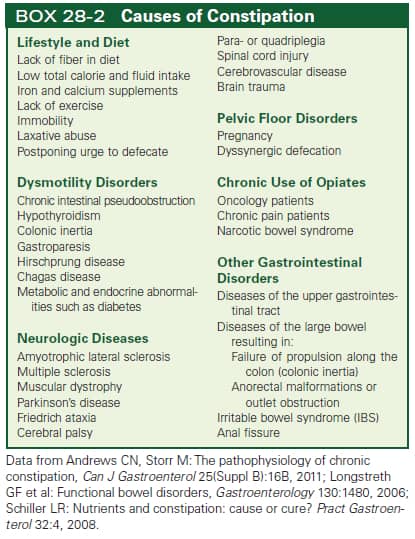

It’s an extremely common condition in the US, and its prevalence only increases with age. The most common causes include:3

- Insufficient fluids

- Low physical activity levels

- Low dietary fiber intakes

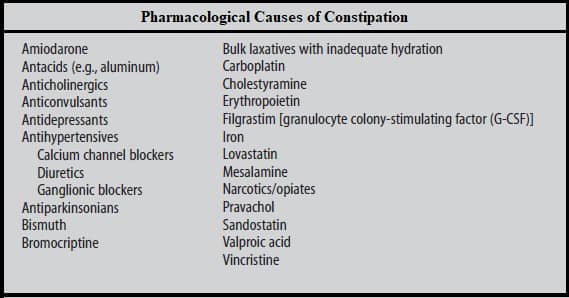

- Medications—antidepressants, narcotics which can slow intestinal transit time. Diuretics can decrease stool moisture.

Other causes include changes to colonic motility that take place with age:3

- Increased collagen deposits in the colon

- “Myenteric” dysfunction—that’s dysfunction of the nerves situated between the muscles of the small intestine

- Reduced nerve input to colonic muscles

- Binding of endorphins to receptors in the intestine.

- Deterioration of the internal anal sphincter

- Loss of elasticity in the rectal wall

- Decreased anal sphincter pressure

Anyway, that’s probably more than you wanted to know.

The Three Types of Constipation

Constipation is classified into primary and secondary constipation. Secondary constipation is related to organic diseases, medications, and systemic diseases.

Since this article pertains to the role of diet in constipation, I won’t be addressing secondary constipation here, as primary constipation is where diet comes into play.

Primary constipation can be further divided into:

- Normal transit—the most common form of chronic constipation. This kind is also known as functional constipation.4

- Slow transit constipation

- Anorectal dysfunction.

When it comes to normal transit constipation, diet is usually implicated.

Functional constipation is considered normal transit because stool passes through the colon in about 5 days (the usual rate) in persons with this condition.

With normal transit constipation, stool frequency is often within the normal range. If it’s normal transit, why is it considered constipation? Because constipation is diagnosed, in part, by patient reports of difficulty defecating and hard stools.

Abdominal discomfort and bloating are normal with this type of constipation. This is where things are a bit paradoxical.

If you read the article gas and bloating, you know these symptoms to be somewhat common on the vegan diet, at least in the beginning. Well, it turns out that there are

As you’ll see, not all types of fiber act in the same manner, or produce the same effects. Symptoms associated with normal transit constipation often respond well to increasing one’s intake of water and certain types of dietary fiber— the soluble, nonviscous fibers.

This goes for children as well. In one study, a lack of fiber was found to be a causative factor in chronic constipation among school-age kids.5 Also, fiber was found to mitigate symptoms of constipation in a group of children.6 It’s worth noting that there are not many studies of this kind.16

Ways in Which Vegan Diets Help Prevent Constipation

Principally, there are three ways the vegan diet helps people avoid constipation:

- Increased intestinal motility/decreased fecal transit time (through the intestine).

- Increased frequency of bowel movements.

- Softer stool consistency.

Increased Intestinal Motility/Faster Transit Times

Intestinal transit time is faster in vegetarians compared to nonvegetarians. For this reason, vegetarians are much less prone to excessively strain during defecation.

Why is this the case? According to Kabeerdoss et al., there’s a marked difference in the gut motility between folks consuming plant-based diets and those consuming omnivorous diets.7

Increased Frequency of Bowel Movements

And by extension, there’s a significant difference in frequency of defecation between various diet groups, with those on plant-based diets having a higher frequency of bowel movements.

Plant-based diets contain higher amounts of complex carbs and dietary fibers than non-vegetarian diets. For this reason, folks who follow vegetarian diets typically have a higher average number of bowel movements per day than non-vegetarians.

The study by Davies et al. cited at the beginning of the article found that people of Kingston, Surrey vegans had higher daily stool frequency than both non-vegetarians and folks on less strict vegetarian diets.2

Likewise, the Prospective Netherlands Cohort Study looked at the proportions of folks from various diet groups having more than two stools per day. It found that 7% of vegetarians to have more than two stools/day compared to 5% of pescatarians and only 3% of non-vegetarians.8

The study also looked at the proportions of people having a stool frequency of fewer than three per week and found the vegetarian group to have the lowest incidence of low stool frequency.

Another large prospective study looked at the relationship between stool frequency and nutritional factors and found vegans to have more daily bowel movements.9

Softer Stool Consistency

In addition to faster intestinal transit times and higher frequency of bowel movements, stool consistency is often softer in vegetarians than in nonvegetarians.

That’s right, vegetarians and vegans are less prone to constipation by either frequency of bowel movements or problems with stool consistency.

Studies like one conducted in eastern India show non-vegetarians to have harder stool and fewer daily bowel movements.10

How does the stool of vegetarians differ? Vegetarian stool is often softer, heavier and more voluminous—likely due to higher insoluble dietary fiber intakes.2

When folks switch to a plant-based diet, it usually results in much higher intakes of fiber overall (both soluble and insoluble), which on balance, leads to softer and more frequent stools.

There are exceptions to this, which are covered under the ways in which vegan diets can cause constipation.

Why Does Fiber Type Affect Stool Softness?

The benefits conferred by insoluble fibers on stool quality are thought to have to do with how this type of fiber hold water.

Ultimately, insoluble fiber increases what’s known as fecal volume or bulk, or stool mass if you will.

Whatever you want to call it, this bulky stool is composed of:

- Unfermented fiber—fiber that the colon never got around to fermenting.

- Salts

- Bacterial mass—generally, fecal bulk increases with bacterial proliferation.

- Water—bacteria are about 80% water. So, when there’s increased bacterial mass, you get a greater water-holding capacity of the feces.

The fiber in wheat bran is one of the most effective laxatives because it can absorb three times its weight in water, which produces a bulky stool.

GI responses to wheat and rice bran include:

- Greater frequency of defecation

- Increased fecal bulk

- Faster intestinal transit time

- Reduced intraluminal pressure.

Other sources of fiber play a role in increasing fecal bulk and decreasing transit time—namely, cellulose, inulin, psyllium, and oligosaccharides.11

Characteristics of Insoluble Fiber

Fiber types can be marketed in various ways, so I’ll list some of the common designations given to the fiber type that’s beneficial in preventing constipation:

- Nonviscous—it holds water but doesn’t bind it into a gel (as does viscous fiber)

- Insoluble—as I’ve been harping on. It doesn’t dissolve in water.

- Non-fermentable or semi-fermentable—the gut bacteria only partially ferment this type of fiber.*

- It’s often known as cellulose—though this is only one type of insoluble fiber. Other types include lignin, hemicellulose, RS1 (resistant starch), carboxymethylcellulose, and various plant waxes

- Food forms often marketed are whole wheat and whole bran.

- Faster transit times leading to more frequent defecations

*Tangentially, this designation is under scrutiny these days as it’s now thought that all fiber is at least somewhat fermentable.12

Anyway, this category of fiber transits the GI tract almost completely unchanged at which point they’re excreted in the feces.

Ways the Vegan Diet Can Lead to Constipation

1) Increased Exposure to Allergens and Food Intolerances

For example, certain high-carbohydrate foods (those containing fructose polymers) and chemicals such as histamines (present in many plant foods) can cause GI problems such as gas, bloating, and diarrhea.

Folks with constipation-specific Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) can have a really hard time with certain food components such as fructose mono-, di-, oligosaccharides. You’ve probably heard of the acronym FODMAP which stands for Fermentable Oligo-, Di-, Mono-saccharides And Polyols.

To know if this is an issue, one need consult with a physician and registered dietitian (RD). Typically, food eliminations, journals, etc. are used to pinpoint the specific offending foods.

2) Eating Lots of Fruit but Neglecting Grains (Raw Vegans, Fruitarians)

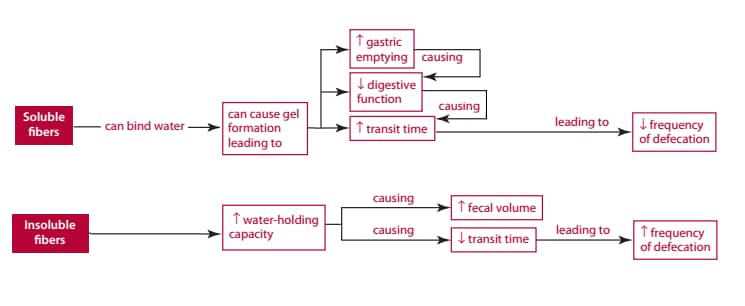

We just spent a lot of time covering insoluble fiber, however, there’s another type of fiber that has healthy, yet opposite effects in the body when it comes to GI transit and defecation frequency.

This type of fiber has the following characteristics:

- Soluble in water—it seems to disappear upon mixing with water

- Viscous—when it mixes in water, it binds water and forms a gel-like consistency.

- Highly/rapidly fermentable—it gets zapped up by your gut bugs and can cause gas and bloating.

- Food forms include fruit—if you want to make homemade jelly, you actually buy a certain type of this fiber known as pectin.

- Slower transit times through the small intestine leading to less frequent defecations

Clearing Up Some Confusion

I said above that insoluble fibers hold water, and now I’m saying soluble fibers bind water. Well, they both attract water in their own way. Soluble fibers bind water forming a gel.

However, water-holding capacity isn’t limited to a fiber’s ability to bind water. Water-holding capacity is also determined by:

- The pH of the GI tract

- The degree of processing the foods have been subjected to

- Fiber particle size. For example, coarsely ground bran, has a higher hydration capacity compared to finely ground bran. The coarse bran with its large particle size holds water and increases fecal volume, which ultimately speeds up the rate of fecal passage through the colon.13

Also, soluble fibers also contribute to stool size in their own way. Fibers such as gums, pectins, and β-glucans (all soluble), may have little effect on stool bulk but they do provide degradation products that promote bacterial proliferation leading to increased stool size.

Source: adapted from Gropper, Sareen S.; Smith, Jack L.. Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism (Page 118).

Fiber Recap

Again, insoluble/nonviscous fibers you find in food sources like whole grain bread speed up intestinal transit, increase stool frequency and reduce the likelihood of constipation.

Soluble fibers like those found in fruit—pectin, etc.—have the opposite effect. They lengthen intestinal transit time, which is what you don’t want.14

Don’t get me wrong, you shouldn’t avoid these foods. They’re very healthy obviously—it’s fruits and vegetables we’re talking about. It’s just a good idea to include a wide variety of high-fiber foods in your diet.

If this is all confusing, don’t worry. I’ve made this handy little flow chart to help clear up some of the confusion.

2) Lack of Water Intake

One problem you can run into when going plant-based is not upping your water intake. Fiber needs water for a smooth transit through the GI tract.

So, one thing that’s sure to result in digestive issues is to double your fiber intake without increasing water intake to match your new needs.

Most people fail to meet daily water recommendations, and it so happens that when you’re on a plant-based diet you just can’t get away with it as easily.

For those 18 years of age and older, the RDI (US) for water intake is 3.7 L/day and 2.71 L/day for men and women, respectively.15

How to Avoid Constipation on the Vegan Diet

Meet Dietary Fiber Recommendations

At minimum.

The general Dietary Reference Intakes (DRI) for fiber consumption is 14 g dietary fiber per 1000 kcal.

Gender-based recommendations are 25g and 38g for adult women and men, respectively. According to Krause’s Food and Nutrition Therapy, “A high-fiber therapeutic diet may have to exceed 25 to 38 g/day.”

Contrast these recommendations with the typical intake of dietary fiber in the US—a mere about 16.2 g/day. No wonder constipation is so common.17

Eat a Wide Range of High-Fiber Plant Foods

To make sure you get a good balance of soluble and insoluble fibers, you’ll want to make sure and eat fruits, vegetables, as well as ample amounts of whole grains, and legumes.

According to L. Kathleen Mahan and Janice L Ramond authors of Krause’s Food and Nutrition Therapy, “Appropriate kinds and amounts of dietary fiber for children, the critically ill, and the very old are unknown.”18

Meet Recommendations for Daily Water Intake

Again, for those 18 years and older, the RDI is 3.7 L/day for men and 2.71 L/day for women.15 At least 2 L is needed to facilitate the effectiveness of high-fiber diets.

As you can imagine, many people don’t meet these recommendations. I often fall short myself. If you’re constipated, you really need to make it a priority. If you’re experiencing constipation since switching to a vegan diet, it’s highly likely that insufficient water intake is the culprit.

Consider Bran Supplements

If you’re an ethical vegan, and not really into the health scene too much, you may prefer to just consolidate your fiber intake into a dose or two per day. If that’s the case, look into over-the-counter fiber bran supplements. They provide a concentrated source of insoluble fiber that we talked about above.

Many of these commercial fiber supplements are quite palatable especially when added to cereals, fruit sauces, soups, and juices.

OTC Mineral Supplement Caution

Certain over-the-counter dietary supplements such as iron, calcium, and antacids have been known to cause constipatoin.23

Source: adapted from Constipation: Aetiology, Evaluation and

Management (Page 16). Springer-verlag

London Ltd. – 2003

null

Make Time for the Important Things in Life (Like Defecation)

It may sound odd, but according to Peter J. Deveaux and Susan Galandiuk of Constipation Etiology, Evaluation, and Management, “a hectic schedule and lack of time to eliminate is an increasingly frequent cause of constipation, particularly in individuals trying to manage more than one job.”19

Get Moving

The effect of physical activity and structured exercise on the GI system is an emerging area of interest.20

What’s the connection? Well, one of the major functions of colonic motor activity is the propulsion of food. While the literature regarding the net effects of exercise on colonic transit is controversial, it seems physical activity may help this process along (adrenaline may bind to the receptors to help get the snake-like motion of the intestines going).21

Enough so that regular physical exercise has been standard as a first-line treatment for primary constipation.22

That pretty much sums up the recommendations. As you can see, they’re similar to the ones you’ll encounter for the general public/non-vegan crowd. If you’re vegan and experiencing constipation, you can be rest assured that it’s not due to a problem that’s inherent to the vegan diet.

References

- Mangels R, Messina V, Messina M. The Dietitian’s Guide to Vegetarian Diets: Issues and Applications. Jones & Bartlett Learning, 3 ed. 2010.

- Davies, G.J., Crowder, M., Reid, B., Dickerson, J.W.T., 1986. Bowel function measurements of individuals with different eating patterns. Gut 27, 164–169.

- Krause’s Food & the Nutrition Care Process (Page 371). L. Mahan-Janice Raymond – Elsevier – 2017

- Christopher N Andrews, and Martin Storr. The pathophysiology of chronic constipation. Can J Gastroenterol. 2011;(Suppl B): 16B–21B.

- Rome E, Adamidis D, Nikolara R, et al. Diet and chronic constipation in children: the role of fiber. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1999;28(2):169-174

- Tse PW, Leung SS, Chan T, et al. Dietary fiber intake and constipation in children with severe developmental disabilities. J Pediatr Child Health. 2000;36(3)236-239.

- Kabeerdoss, J., Devi, R.S., Mary, R.R., Ramakrishna, B.S., 2012. Faecal microbiota composition in vegetarians: comparison with omnivores in a cohort of young women in southern India. Br. J. Nutr. 108, 953–957.

- Gilsing, A.M.J., Weijenberg, M.P., Goldbohm, R.A., Dagnelie, P.C., van den Brandt, P., Schouten, L.J., 2013. The Netherlands Cohort Study – meat Investigation Cohort; a population-based cohort over-represented with vegetarians, pescetarians and low meat consumers. Nutr. J. 12, 156.

- Sanjoaquin, M.A., Appleby, P.N., Spencer, E.A., Key, T.J., 2003. Nutrition and lifestyle in relation to bowel movement frequency: a cross-sectional study of 20 630 men and women in EPIC–Oxford. Public Health Nutr. 7 (1), 77–83.

- Panigrahi, M.K., Kar, S.K., Singh, S.P., Ghoshal, U.C., 2013. Defecation frequency and stool form in a coastal eastern indian population. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 19 (3), 374–380.

- Gropper, Sareen S.; Smith, Jack L.. Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism (Page 123-124).

- Gropper, Sareen S; Smith, Jack L. Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism (Page 123).

- Gropper, Sareen S.; Smith, Jack L.. Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism (Page 117).

- Gropper, Sareen S.; Smith, Jack L. Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism (Page 119).

- US daily reference intake values Archived 2011-10-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- Kranz S, Brauchla M, Slavin JL, et al: What do we know about dietary fiber intake in children and health? The effects of fiber on constipation, obesity, and diabetes in children, Adv Nutr 3:47, 2012.

- Grooms KN, Ommerborn MJ, Pham DQ, et al: Dietary fiber intake and cardiometabolic risk among US adults, NHANES 1999-2010, Am J Med 126:1059, 2013

- Krause’s Food & the Nutrition Care Process (Page 528). L. Mahan-Janice Raymond – Elsevier – 2017

- Constipation: Aetiology, Evaluation and Management (Page 15). Springer-verlag London Ltd. – 2003

- Peters HP, De Vries WR, Vanberge-Henegouwen GP, Akkermans LM. Potential benefits and hazards of physical activity and exercise on the gastrointestinal tract. Gut 2001;48:435–439.

- Rao SS, Beaty J, Chamberlain M, Lambert PG, Gisolfi C. Effects of acute graded exercise on human colonic motility. Am J Physiol 1999;276(5 pt 1):G1221–1226.

- Camilleri M, Thompson WG, Fleshman JW, Pemberton JH. Clinical management of intractable constipation [comment]. Ann Intern Med 1994;121:520–528.

- Data from Andrews CN, Storr M: The pathophysiology of chronic constipation, Can J Gastroenterol 25(Suppl B):16B, 2011; Longstreth GF et al: Functional bowel disorders, Gastroenterology 130:1480, 2006; Schiller LR: Nutrients and constipation: cause or cure? Pract Gastroenterol 32:4, 2008.

- Santosh Singh Bhadoriya, et al. Tamarindus indica: Extent of explored potential. Pharmacogn Rev. 2011 Jan-Jun; 5(9): 73–81. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3210002/

- Dalziel JM. The Useful Plants of West Tropical Africa.London: Crown Agents for Overseas Governments and Administrations. 1937:612.

- Food-related behaviors during drought: a study of rural Fulani, northeastern Nigeria. Lockett CT, Grivetti LE Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2000 Mar; 51(2):91-107. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10953753/